Surfing on wooden surfboards really got underway in Peru around the time of World War II.

What follows is a complete history of that period, the years afterwards and the trace back to Peru's earliest surfing history.

This chapter is also available as an eBook for $2.95 by clicking on the Paypal link below. The advantage of the eBook is that it is completely portable and can be shared and passed on to others. Importantly, the hyperlinks embedded in the book make navigation very easy and vintage Peruvian photos are included:

The Early History of Peruvian Surfing

By

Malcolm Gault-Williams

Contents

Introduction

Peru is rich in surf history. While we can only conjecture as to its earliest days of riding reed craft, the stories of the early days of Peru’s modern era are now legendary across the planet.

I am indebted to the following for their contributions to this 23,069-word look at the early days of modern Peruvian surf history:

First and foremost is Oscar Tramontana Figallo, whose work in documenting Peruvian surf history was invaluable. Coming a close second is Felipe Pomar, who took time out to answer specific questions I had about his early days and the nature of Peruvian surfing especially in the 1960s. Thirdly, I am in much appreciation of the archival photos from Carlos Rey y Lama (viewable in the eBook version).

Although I credit everyone in my footnotes, I also want to thank – in the order of the appearance of their contributions – the following: Matt Warshaw, Ben Finney and James Houston, Peru Surf Guides, Glenn Hening, Marcus Sanders, Olas Peru, Fred Hemmings, Mike Doyle, Augusto Villaran, Oscar M. Brain and Juan Forero.

I hope you enjoy this chapter as much as I did writing it!

Aloha,

Santa Barbara, California, USA, April 2010

Pre-Inca Wave Riding

Off the west coast of South America, Pacific ground swells hit the beaches from Panama to Patagonia, producing some of the planet’s best surf. Peru, South America’s third-largest country, has a rich surfing history to go with its 1,500 miles of mostly dry and rugged Pacific-facing coastline.

“The surf in Peru is remarkably consistent,” wrote Matt Warshaw in the

Encyclopedia of Surfing,“with wave height averaging between three to six foot throughout the year, thanks to long-distance north swells during the summer, a steady feed of powerful south swells in winter, and a balance of the two during spring and fall. About 80 percent of Peru’s surf spots are lefts, most of them breaking along rocky points spilling onto sandy beaches. Daytime coastal air temperatures generally range between the low 70s in summer and the low 60s in winter; water temperatures around the capital city of Lima, chilled by the Humboldt current, range from the upper 60s to the mid-50s.”

1Surfing in Peru is centered in Lima – home to one-fifth of the country’s total population. “Peru’s wave-rich northern tip faces northwest (the rest of the coast faces southwest), warmed by the Panama Current, is home to an assortment of points and reefs, including the high-acceleration tubes at Cabo Blanco, Chicama – the arid left-breaking point known as the longest ocean wave in the world, with rides sometimes lasting more than a mile – is located about 200 miles south of Punta Negra, and is flanked by at least four other high-quality breaks. Lima’s Pico Alto is the country’s premier big-wave spot, with well-shaped rights and lefts (rights preferred) breaking up to 25 feet. The country’s southern coast is lightly populated, hard to access, and rarely surfed. The number and quality of surf breaks, however, is thought to be nearly equal to that found in the north.”

2

In addition to this surf wealth, the ancient land now known as Peru has the oldest documented tradition of wave riding.

Caballitos de Tortora

In relatively recent years, Peruvian world champion surfer Felipe Pomar has lead the charge for greater recognition of Peru’s wave riding heritage. Taking it a step further, Felipe has joined with a few surfing and non-surfing historians to argue that surfing as a sport originated in what is now called Peru. They point to the fact that pre-Inca fishermen were riding surf as far back as 3,000 B.C., riding waves on what Spanish conquistadors called caballitos (little horses) made of bundled reeds. This would put the Peruvians about a thousand years before the earliest estimates for surf riding in Hawai‘i.

The conventional history of surfing, of course, has it originating as a very basic type of wave riding originating in the western Pacific Ocean. Under this scenario,

the first surfers were Polynesian or Polynesian ancestors. If one is to discount that surfing probably began before the Polynesians reached the Hawaiian Islands, then surfing began sometime between 2000 B.C. and 400 A.D.

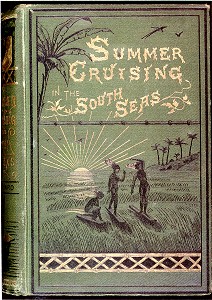

3University of Hawai‘i anthropology professor and early surf historian Ben Finney acknowledged that surfing was not limited to Polynesia. In his

Surfboarding in Oceania: Its Pre-European Distribution, Finney wrote that an “extensive examination of the available sources has shown that surfboarding was known in Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. In fact, surfboarding was practiced in Oceania from New Guinea in the West, to Easter Island in the East, and from Hawai‘i in the North to New Zealand in the South.” Finney cited sightings of various forms of primitive surfing in places as diverse as Owa Raha in the Solomon Islands (observed in 1949); to Yap in the Western Carolines (observed by a colleague); and south in the New Hebrides and Fiji. “With reservations,” Finney concluded, this “wide distribution would seem to indicate that surfboarding is a general Oceanic sport, rather than a specifically Polynesian sport.”

4Decades after writing the foregoing, however, Finney clarified that – lest one be easily tempted to look elsewhere than Polynesia for surfing’s earliest roots – “Indigenous board-surfing in the Pacific was most highly developed on islands within the Polynesian Triangle bounded by Hawai‘i, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and Aotearoa (New Zealand). Early reports of surfing along the shores of islands from New Guinea to Polynesia indicate that this sport, at least in its rudimentary form, was part of the common heritage of the seafaring people who spread across the Pacific thousands of years ago.”

5

So, if Polynesian surfing began before people reached the Hawaiian Islands, it is certainly older than 3,000 years ago. The fact is, we just don’t know how old surfing in eastern Polynesia is, let alone how old it is in western Polynesia. Could pre-Polynesians have surfed? It’s most certainly probable, even if it was merely bodysurfing, bodyboarding or canoe surfing.

In fact, anywhere on the planet that has surf, a moderate or temperate climate, and coastal populations of humans engaged in fishing, there must have been surfers – if only riding surf in canoes as part of work or recreationally. Also, the tendency of young peope to get into the ocean and bodysurf is a universal act. Many historians wishing to blaze new ground often forget this most obvious aspect of coastal living in all ages and all temperate coasts.

We are fortunate that the coastal Peruvians, very early on, developed ceramic art to a high degree early in their history because they left an actual record of their surfing behind. In the museum of the Peruvian city of Chan Chan, there is pottery showing Huanchaco people “running waves” on reed rafts we now call caballitos de totora (little horses of the totora reed). These reed mats were and still are used primarily for fishing, but the pottery also indicates they were also used for fun; to ride the breaking waves of the northwest coast of Peru. Dating of the ceramic artifacts prove that wave riding on reed boats existed in that country as early as 3000 to 4000 B.C., long before the Spanish invasion in the 16th Century and well before the founding of the the Incan Empire in the 13th Century.

The two ancient pre-Inca cultures, Mochica and Chimu, developed in the north of Peru more than two thousand years ago. These were the first Peruvian societies to relate actively with powerful coastal tidal zones, through fishing and transport. The people of these societies left us many examples of designs featuring waves in their religious iconography and their art expressed on textiles, frescos and ceramics.

The first Peruvians to ride waves were no doubt fishermen who had to traverse often powerful ocean waves in order to get food. Peruvians are still using the reed craft their ancestors used thousands of years ago, now in modern times. It is possible to watch them in Trujillo; Huanchaco Beach is famous for this reason.

6“In 1987,” Matt Warshaw wrote, “[Felipe] Pomar began a one-man crusade to have the fishermen of ancient Chan Chan, a pre-Inca empire located in what is now Peru’s northern territory, recognized as the original surfers. Chan Chan fishermen from as far back as 3,000 B.C., Pomar said, used reed-built

caballitos (‘little horses’) to ride waves; a 15

th-century warrior, furthermore, on a seagoing mission to expand Inca territory, may have introduced the

caballito– and surfing – to Polynesia. ‘While there is much room for speculation,’ Pomar said in a surf magazine article, ‘there seems to be a distinct possibility that the embryonic form of modern-day surfing was born off the coast of northern Peru.’”

7“In Northern Peru,” Felipe told me, “there is pottery that shows people paddling on a surfboard-like one-man boat, paddling with their arms. There is archeological evidence that people were doing that as far back as 5,000 years ago... They're called

caballitos de totora. ‘

caballitos’ means ‘little horses’ and ‘

totora’ is a certain kind of reed. The Spanish Conquistadores named the little reed surfboards – or the reed kayaks; they're somewhere between a surfboard and a kayak – they named them ‘caballitos’ because when they witnessed them riding waves on one of these

caballitos, they were used to riding horses and they saw them riding in with the surf, so they called them ‘little horses.’”

8

Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002)

Pomar’s perspective was shared by Thor Heyerdahl (October 6, 1914, Larvik, Norway – April 18, 2002, Colla Micheri, Italy), the Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a scientific background in zoology and geography. Heyerdahl became notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition of the late 1940s, when he sailed 4,300 miles (8,000 km) by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands.

Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki Expedition is important in the discussion of Polynesian dispersion across the Pacific, although its premises runs counter to prevailing theory. Heyerdahl and five fellow adventurers went to Peru, where they constructed a pae-pae raft from balsa wood and other native materials, a raft that they called the Kon-Tiki. The Kon-Tiki expedition was inspired by old reports and drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadors of Inca rafts, and by native legends and archaeological evidence suggesting contact between South America and Polynesia. After a 101 day, 4,300 mile (8,000 km) journey across the Pacific Ocean, Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki smashed into the reef at Raroia in the Tuamotu Islands on August 7, 1947.

Kon-Tiki demonstrated that it was possible for a primitive raft to sail the Pacific with relative ease and safety, especially to the west (with the wind). The raft proved to be highly maneuverable, and fish congregated between the two balsa logs in such numbers that ancient sailors could have possibly relied on fish for hydration in the absence of other sources of fresh water. Inspired by Kon-Tiki, other rafts have repeated the voyage. Heyerdahl's book about the expedition, Kon-Tiki, has been translated into over 50 languages. The documentary film of the expedition, itself entitled Kon-Tiki, won an Academy Award in 1951.

“Anthropologists continue to believe,” Wikipedia’s history of the expedition states, “based on linguistic, physical, and genetic evidence, that Polynesia was settled from west to east, migration having begun from the Asian mainland. There are controversial indications, though, of some sort of South American/Polynesian contact, most notably in the fact that the South American sweet potato served as a dietary staple throughout much of Polynesia. Heyerdahl attempted to counter the linguistic argument with the analogy that, guessing the origin of African-Americans, he would prefer to believe that they came from Africa, judging from their skin colour, and not from England, judging from their speech.”

“Heyerdahl claimed that in Incan legend there was a sun-god named Con-Tici Viracocha who was the supreme head of the mythical fair-skinned people in Peru. The original name for Virakocha was Kon-Tiki or Illa-Tiki, which means Sun-Tiki or Fire-Tiki. Kon-Tiki was high priest and sun-king of these legendary ‘white men’ who left enormous ruins on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The legend continues with the mysterious bearded white men being attacked by a chief named Cari who came from the Coquimbo Valley. They had a battle on an island in Lake Titicaca, and the fair race was massacred. However, Kon-Tiki and his closest companions managed to escape and later arrived on the Pacific coast.”

9“When the Spaniards came to Peru, Heyerdahl asserted, the Incas told them that the colossal monuments that stood deserted about the landscape were erected by a race of white gods who had lived there before the Incas themselves became rulers. The Incas described these ‘white gods’ as wise, peaceful instructors who had originally come from the north in the ‘morning of time’ and taught the Incas’ primitive forefathers architecture as well as manners and customs. They were unlike other Native Americans in that they had ‘white skins and long beards’ and were taller than the Incas. The Incas said that the ‘white gods’ had then left as suddenly as they had come and fled westward across the Pacific. After they had left, the Incas themselves took over power in the country.”

10

“Heyerdahl said that when the Europeans first came to the Pacific islands, they were astonished that they found some of the natives to have relatively light skins and beards. There were whole families that had pale skin, hair varying in color from reddish to blonde. In contrast, most of the Polynesians had golden-brown skin, raven-black hair, and rather flat noses. Heyerdahl claimed that when Jakob Roggeveen first ‘discovered’ Easter Island in 1722, he supposedly noticed that many of the natives were white-skinned. Heyerdahl claimed that these people could count their ancestors who were ‘white-skinned’ right back to the time of Tiki and Hotu Matua, when they first came sailing across the sea ‘from a mountainous land in the east which was scorched by the sun.’ The ethnographic evidence for these claims is outlined in Heyerdahl’s book Aku Aku: The Secret of Easter Island.”

“Heyerdahl proposed that Tiki’s neolithic people colonized the then-uninhabited Polynesian islands as far north as Hawaii, as far south as New Zealand, as far east as Easter Island, and as far west as Samoa and Tonga around 500 CE. They supposedly sailed from Peru to the Polynesian islands on

pae-paes– large rafts built from balsa logs, complete with sails and each with a small cottage. They built enormous stone statues carved in the image of human beings on Pitcairn, the Marquesas, and Easter Island that resembled those in Peru. They also built huge pyramids on Tahiti and Samoa with steps like those in Peru. But all over Polynesia, Heyerdahl found indications that Tiki’s peaceable race had not been able to hold the islands alone for long. He found evidence that suggested that seagoing war canoes as large as Viking ships and lashed together two and two had brought Stone Age Northwest American Indians to Polynesia around 1100 CE, and they mingled with Tiki’s people. The oral history of the people of Easter Island, at least as it was documented by Heyerdahl, is completely consistent with this theory, as is the archaeological record he examined (Heyerdahl 1958). In particular, Heyerdahl obtained a radiocarbon date of 400 CE for a charcoal fire located in the pit that was held by the people of Easter Island to have been used as an ‘oven’ by the ‘Long Ears,’ which Heyerdahl's Rapa Nui sources, reciting oral tradition, identified as a white race which had ruled the island in the past (Heyerdahl 1958).”

11“Heyerdahl further argued in his book

American Indians in the Pacific that the current inhabitants of Polynesia migrated not from an Asian source, but via an alternate route. He proposes that Polynesians traveled with the wind along the North Pacific current. These migrants then arrived in British Columbia. Heyerdahl called contemporary tribes of British Columbia, such as the Tlingit and Haida, descendants of these migrants. Heyerdahl claimed that cultural and physical similarities existed between these British Columbian tribes, Polynesians, and the Old World source. Heyerdahl’s claims aside, however, there is no evidence that the Tlingit, Haida or other British Columbian tribes have an affinity with Polynesians.”

12As intriguing as Heyerdahls’ theory of Polynesian origins is, it has never gained acceptance by anthropologists.

13 Physical and cultural evidence has long suggested that Polynesia was settled from west to east, migration having begun from the Asian mainland, not South America. In the late 1990s, genetic testing found that the mitochondrial DNA of the Polynesians is more similar to people from Southeast Asia than to people from South America, showing that their ancestors most likely came from Asia.

14 Easter Islanders are of Polynesian descent.

15

Glenn Hening, Surfrider founder, president of the Groundswell Society, agrees that Peruvians could have been the first of what we might term “surfers.” Hening travelled to Peru to experience

las caballitos de totora first-hand. Although he agrees Peruvians might have been the “first surfers,” he is not willing to go as far as Felipe Pomar. In a personal email to Pomar, in 2009, Hening pointed out that “Your theory about surfing craft being developed first, and from them then fishing craft, simply cannot be supported by the evidence. The evidence is that reed craft were being used up to 3,500 years ago to provide food for the large populations at Caral, Chan Chan, Tucume, etc. Your evidence of personal craft is only 1200 years old – and consists of the two ceramics at the Breuning Museum.”

16“… my contention,” Felipe responded, “is not that they were first built to have fun and then improved for fishing. My contention is that more important than having fun, or even fishing, was surviving.

17

“The design tells me they were designed to ride waves. The reason riding the wave was so important is because to make it safely to the beach from outside (the ocean side of the breaking waves) you had to avoid getting caught by a set of breakers.

“If you got caught you could drown, or lose your fish (if you had been fishing).

“Riding the wave enabled the Caballito rider to rapidly ride a wave in and avoid getting smashed and upended/capsized by the waves. Riding a wave kept him out of harms way. Thus the Caballitos were designed to ride waves and used for fishing (by the fishermen), recreation (by the sons of the fishermen), and sport (by warriors, priests, chiefs, or others with free time seeking fitness, sport, or power).”

18As Thor Heyerdahl observed: “Knowing the people on the coast today, this would be the first place where surfing could have developed. 5000 years ago, they were mentally and physically exactly like us. They would do precisely as you and I do. If we have time for leisure – and in those days the royalty on the coast had all the leisure time they could ask for – there’d be nothing more natural than for them to start surfing in these waves.”

19

“In areas of constant surf,” Felipe Pomar maintains, “the people had to design a unipersonal boat that could get them through the braking waves (to beyond the breaking waves) and then through the breaking wave zone to get back to shore. Riding the wave was the safest, fastest, and often the only way to get back to shore.

“The Caballito is [the pre-Incan]… design for areas with constant surf where you have to ride the wave to get back to shore. Look at the design on the caballito: length, width, scoop, bottom contour. Compare it to older surfboard design’s and Kayak’s made for riding waves. You can’t avoid seeing that the Caballito was designed to ride waves of the sea. And it is extremely sophisticated and functional considering when it was developed and the materials they had to work with.”

20“In my opinion,” continued Felipe, “what Peru has is the kind of ideal coastline for riding waves to develope and whether they were riding them on a reed

caballito or riding them on some other kind of plank or just bodysurfing, the constant surf on the Peruvian coast is, in many places, like Waikiki. You know, you have the rollers coming in from way out and you can catch them and ride for long distance. So, for that reason, it’s perfectly understandable that surfing – riding waves – would develop on that kind of coastline.”

21“It is important that the Peruvians know our history in regard to Totora Horse,” Felipe Pomar emphasized.

22

Peruvians and the Sea

“There is no doubt that Peruvian societies going back almost 3500 years had used the ‘caballitos’ (Spanish for ‘little horses’) for fishing purposes,” wrote Glenn Hening in “Riding Waves Two Thousand Years Ago,” “and Heyerdahl told us in an interview that those societies would have enjoyed the surf just as we do. Dr. Heyerdahl had also developed theories about ancient Peruvians sailing to Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and had confirmed the existence of stone sculptures found there depicting reed boats. Coupled with research connecting Rapa Nui to the rest of Polynesia through the ‘wayfinding’ voyages, a tenuous link could be made from Peru to Polynesia to Hawai‘i.

23

Hening points to the relationship ancient Peruvians seemed to have with the ocean. “Peruvian cultures had an almost religious relationship with waves,” Glenn wrote, “… It may be very difficult to prove surfing came to Hawai‘i from Peru, but with more research in the ruins of temples and cities along the coast of northern Peru, we should eventually find definitive evidence that people were riding waves there at least a thousand years before any evidence exists of surfing in Hawai‘i. Why? Because we already have proof that riding a reed boat, and not using it for fishing, was a concept not unknown to the ancient Peruvians.

“When I say ancient Peruvians, I am talking about societies that existed before the Incas. The ruins at Machu Pichu are famous around the world, and for most people, the Incas represent the history of Peru before the arrival of the Spanish. However, there were well-developed cultures prior to the Incans, and huge cities, temples and pyramids can be found along the coast of Northern Peru that pre-date the Incas by hundreds, and in two cases, thousand of years.”

24“Those societies,” Glenn went on, “notably the Chimu and the Moche, depended largely on the ocean for their protein, and for them the ocean was a mystical place of unlimited power. They repeatedly used waves as a design element in their clothing, jewelry, and architecture. In fact, a ceremonial courtyard found in the Chan Chan ruins, not more than a kilometer from the surf, is ringed by walls covered with parallel lines, the purpose of which was to surround the people participating in the ceremonies with the power of the sea. In this case, waves were used to decorate a ‘church’, and in other societies pre-dating Chan Chan waves were used on the golden crowns of kings and their clothing. And one priesthood used waves as the symbol of their power as they exerted a strong influence over the government and daily lives in cities of up to 50,000 people.”

25

“To me,” Glenn Hening wrote, “the veneration of waves by ancient Peruvians is entirely understandable. In fact, surfers everywhere cover their walls with pictures of swells, tubes, and rolling waves. It was breathtaking to visit a temple that was built overlooking a left point break along the coast north of Huanchaco and see waves six feet high carved in an endless chain along a wall still not full excavated. As a surfer, to touch those waves, even as I could hear the roar of real surf off in the distance, was as important an experience for me...”

For Glenn Hening, his conversion to viewing Peruvians as the first surfers came when he viewed “A ceramic, possibly almost 1200 years old… unearthed in 1938 by a German archaeologist, Franz Wasserman.” This ceramic “depicts a Peruvian god riding the crescent moon across the night sky, and the moon was drawn in the form of a reed boat. To me, that indicates the artist, whoever he or she was, conceived of using a reed craft for something that we could call ‘surfing.’

“Now, other evidence exists of the use of reeds to built small ‘floats’ for going out in the surf to complete ‘rites of passage’ ceremonies, given the strength and courage it takes to challenge the endless lines of surf that hit the coast of Peru. But the god riding his ‘moonship’ was a very exciting step forward in the search for the first surfer.

“As a result, I strongly believe that with more research and archaeological investigations at sites in Northern Peru, there is a good chance of finding conclusive proof that ancient Peruvians were using reed craft not only for fishing, but also recreational purposes. As Dr. Heyerdahl said, ‘People haven’t changed in fundamental ways for thousands of years, and if something is fun for us, it certainly would have been fun for them. And that includes surfing.’”

Speaking personally, Glenn wrote, “As a surfer, my memories of my trips to Peru are filled with visions of endless waves to the horizon, long walls of peeling tubes that I could ride for hundreds of meters, and the roar of surf all day and all night. As a professional historian, I was fascinated by the reed boat ceramics and the use of waves to decorate royal clothes, temples, and artwork found at many archaeological sites...”

26“When Hening started researching the coastal cultures of Northern Peru,” wrote Marcus Sanders in “Lines in the Dust – The Groundswell Society Goes to Peru 2002,” published in

The Surfer’s Path,“around the fishing town of Huanchaco (about 500 miles north of Lima), he started questioning the entrenched idea that surfing began in Hawai‘i. He wasn’t the first. Some surfing historians – including Peruvian businessman and cultural historian Fortunato Quesada and Peru’s ex-world champion, Felipe Pomar – assert that the ancient Peruvians took to the waves in their ancient reed craft (called

caballitos, or “little horses”) thousands of years ago. But Hening has been one of the most diligent in researching the possibilities, especially in the last couple of years.

27“… In 1994, after getting fairly fed up with Surfrider’s continual shift away from what he saw as its original vision – that is, a ‘Cousteau Society for surfers’ – Hening decided to create the Groundswell Society, which was intended to be a kind of non-corporate surfing think tank…”

28

“Hening’s third question, about the history of the place, can be found in the elaborate architecture, ceramics and drawing of ancient Peruvians on display in the museums and various archaeological sites along the coast. It should come as no surprise that everything had a deep maritime influence, with examples of curling waves, breaking waves, lines to the horizon and peeling pointbreaks. There’s even a 2000-year-old temple located right on a cliff above a Honolua Bay-style left. ‘They didn’t’ build in the middle of the beach,’ Hening points out. ‘They built it right where there were lines bending in and peeling perfectly.’”

“Surfing’s direct influence is one thing,” Glenn acknowledged. “Having one’s life defined by the power of the ocean is something a little different. Surfing is a small part of our relationship with the ocean. These cultures needed the ocean to eat, but they also recognized the geometry of waves, and situated their temples not at close-out surf, but at perfect points. They were cognizant of how waves break. And they were cognizant of curling waves, of tubes – you can see it in their architecture; there are ‘Moche’ ceramics dating back to AD 200 that depict a deity riding the crescent moon as if it was a reed boat. Of course, there’s more research to be done – nothing’s been proven. But every year more and more sites are being discovered that give us more information about how people’s lives were informed by waves thousands of years ago.”

29When asked about how Polynesians and, in particular, Hawaiians felt about the Peru theory as first point for surfing, Felipe Pomar responded, “A few might like, and some not, but… There is no doubt that the art of surfing was born on the coast of Peru. This is because the former

caballitos were running waves in Peru thousands of years before there were settlers in the islands of Hawaii. It is also true that in Hawaii, the art developed rapidly with new materials, and the exceptional conditions of their sea. But the oldest examples of people running waves have them in Peru.”

30

Modern Era of Peruvian Surfing Begins

As for modern Peruvian surfing, it can be traced back as early as 1909. According to an article published in the newspaper

El Comercio, February 28, 1960, “The origins of this activity in Peru can be found in what our water sport people call ‘riding waves.’ It was then, by 1909, that the group conformed by Alfonso and Alfredo ‘Shark’ Granda Pezet, the old Buzzaglo, Celso Gamarra, the ‘Gringo’ Schoeder and Alfonso Cillóniz, among others, engaged in ‘riding waves’ using a drawing board, in front of the beaches of Barranco. A little bit later, they were replaced by table boards.”

31By the early 1920s, there were still surfers at Barranco, north of Lima, riding “homemade boards” that were featured in a 1924 issue of

Aire Libre, a Peruvian sports magazine.

32 Surfing probably continued, perhaps on-and-off, until the 1930s.

“I’ve heard that there was some limited surfing at Barranco before Carlos Dogny reintroduced surfing in Peru,” Felipe Pomar told me. “A magazine has been found, dated January 9th, 1924, which has a picture of somebody standing on a board, surfing a wave, at ... Barranco. I have surfed that area. There is a beach club there called ‘Regatas’ and there is a perfect little wave that runs along a point. It’s great for bodysurfers and a lot of the members of that club would go to that beach and bodysurf. They would also bodyboard and it seems that in 1924, there was a group of friends who made themselves a larger bodyboard and they were standing on it [surfing].”

33

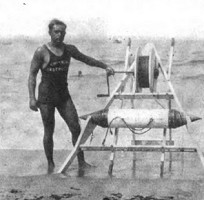

Carlos Dogny (1909-1997)

Surfing on boards in Peru came back to life after 1938, when a Peruvian visitor to Hawai‘i by the name of Carlos Dogny [doan-NEE] Larco fell in love with the sport of the

Hawaiian kings. Dogny visited Hawai‘i several times, bringing back a board given him by

Duke Kahanamoku. In his home country, Dogny introduced his friends to the sport and it has been alive and thriving there, ever since.

34“In Peru and many Latin American countries, the last name – the father’s name – would be the second name,” Felipe clarified for me when I asked him about Carlos Dogny. “Instead of adding ‘junior,’ they add the mother’s maiden name. So, in Peru, you would use ‘Carlos Dogny Larco.’ In the U.S., you would use ‘Carlos Dogny’ ... Adding the ‘Larco’ would be very confusing.”

35Carlos Dogny is described in the

Encyclopedia of Surfing as a “Wealthy gentleman surfer and socialite from Lima, Peru, the founder of Club Waikiki, and often referred to as the father of Peruvian surfing.”

36

“Dogny was born (1909) in Barranco, the only son of a French army colonel and a Peruvian sugarcane heiress,” Matt Warshaw wrote, “and grew up in both Lima and the beachside resort town of Biarritz, France. In 1938, the 29-year-old Dogny traveled with a French polo team to Honolulu, where he learned to surf in the gentle waves at Waikiki. Hawaiian surf legend

Duke Kahanamoku gave Dogny a heavy wooden board to take back to Peru; on the beach at Miraflores, on the outskirts of Lima, Dogny passed the board around to a group of similarly wealthy friends… Dogny and his small band of wave-riders have long been thought of as the original Peruvian surfers.”

37“Carlos Dogny was a globetrotter, playboy and sportsman,” acknowledged fellow Peruvians, “who circled the globe 39 times. One of his favorite sports was polo, and thanks to this, he was invited to visit Hawaii. There he learned to surf the traditional sport of kings and military chiefs with the Ambassador of Modern Surfing, Duke Kahanamoku. He named it ‘tabla hawaiana’ (Hawaiian board), and the name still holds in Peru. It required a lot of physical strength, because at that time boards were 5 to 6 meters long, of solid wood and weighed 100 kilos.”

38“During his studies in New York, the Second World War began in Europe. Even though he was a Peruvian citizen, he could have been sent to war, because he lived in the USA. To avoid this, he chose the place he found more secure and pleasant: Hawaii. But once there, he had the feeling that his life was in danger, too, because the war expanded all over the world and there was war between Japan and the USA. Due to the turmoil, he came back to South America, bringing with him by ship, one of those big boards. When he arrived in Lima he started to study the sea and [found good surf in]… Miraflores… Later on, curious swimmers came close to him while he surfed, and he taught them this new sport. Such was the interest they showed, that the most enthusiastic ones begun to produce their own boards made of wood in workshops and garages. Since there was no place to leave the boards after surfing, the famous Waikiki Club in the ‘Costa Verde’ (Green Coast) of Miraflores was established. He also was an important member in the creation of the first French surf club.”

39“The surf world’s original aristocrat organization and the long time hub of Peruvian surfing Club Waikiki,” wrote Matt Warshaw, “was founded and built in 1942, with Dogny serving as club president. In 1959, Dogny and French surfer Michel Barland cofounded the Waikiki Surf Club, France’s first surfing organization, in Biarritz. Dogny died in 1997, age 87; his ashes were spread in the ocean in front of Club Waikiki.”

40“Carlos Dogny Larco is indisputably the father of our sport in Peru,” attested Felipe Pomar. “I was lucky to meet and develop a friendship with him that lasted many years. He was a person of high society and he had a wonderful life. He circled the world… always following the summer and sun. As founder of Club Waikiki, he had a great positive influence on many people, myself included.”

41“I probably met Carlos [Dogny] as soon as I became member of Club Waikiki, when I was 14,” Felipe Pomar told me. “Carlos would have been around 48 [at that point]. Of course, when I first met him, he was just this older gentleman who was the founder of the club and the person that had brought modern surfing to Peru.”

42

“Carlos was a real gentleman,” Felipe continued. “He was very out-going. He had a great education. He was extremely well-traveled. To give you an example, he only liked to spend the summers in Peru. He would follow the summer around the world. He probably did that... for over 30 years.

“He was a sportsman and he loved the beautiful women. He has been called ‘The King of the Peruvian Playboys.’ He loved the ocean, sports, and beautiful women. He said in one article that he loved the ocean and the sun and his entire life has been a summer.”

“He always told me that having balance in life is very important. And what he meant by that was that sports and surfing were great, but you should also have a business side to your life, with a social side and a spiritual side. He felt it was very important to have a balanced life.”

“He learned to surf in Waikiki in the late ‘30s and the board that he took back to Peru when he left Hawaii was a

hollow Blake finless surfboard that weighed approximately 100 pounds. In the beginning, he used to surf with tennis shoes because in Peru, the beaches are made of big cobblestones, at least at the beaches where surfing first started – Club Waikiki... I remember him riding big boards and competing in tandem competitions...

“I never saw him go to Kon-Tiki or Punta Rocas, which were our big wave spots, but... in the 1970s, he visited me on Kauai and he broke a rib surfing Hanalei. It was a fairly big day and I advised him not to surf. He said he just wanted to come out and kind of look at the waves from closer up. Of course, once he paddled out and looked at the waves from closer up, he decided to catch ‘em. He got hit by surfboard and broke a rib.

“To kind of give you an idea about the kind of guy that he was, he was in great pain. We were staying at the Club Med, which was at Hanalei back then. Somehow he got into a conversation with a pretty girl that worked there and she asked him what kind of work that he did. I remember him smiling and telling her that he was a secret agent [laughs]. So, he had a good sense of humor, too.”

43

Club Waikiki

Carlos Dogny founded Club Waikiki, at Miraflores, outside of Lima, in 1942. The timing was good, as “a local furniture company [had begun]… producing a small number of hollow paddleboard/surfboards.” From the outset, Club Waikiki surfers were affluent and drawn from the upper tiers of Peruvian society. They generally shunned locally made boards, preferring to ride imports from California or Hawai‘i. The country’s first surf shop didn’t open until 1975.

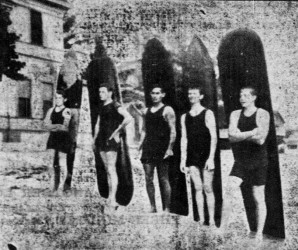

44Even twenty-four years later, “Due to the country’s economic conditions, participation in the sport has been limited to the wealthier class… It was the young men of this well-to-do class, already interested in beach recreations, who quickly took up surfing and have continued to support it. Today,” Finney and Houston wrote in 1966, “Peruvian surfing is characterized by a luxury found nowhere else in the surfing world… most surfers belong to the swank ‘Club Waikiki’ on the beach at Miraflores, only fifteen minutes from Lima. It was founded in 1942 by Senor Dogny and three other surfing Peruvians. Much like a yacht club in appearance, the club is equipped with fish ponds, gardens, a squash court for winter recreation, a kitchen, bar, and clothes-changing facilities; it also provides members with the services of ‘board boys’ who fetch and carry surfboards to and from the water.”

45Club Waikiki was an “Elegant, class-conscious Peruvian beachfront surfing club located in Miraflores, the wealthiest suburb in Lima,” wrote Matt Warshaw, adding that even in the 2000s, “Surfing in Peru was (and in large part remains) a pastime for the wealthy, and the sport here evolved in and around the hushed and expensively accoutered rooms and patios of Club Waikiki.”

46

The club had black-tied waiters and hired ‘beachboys’ who applied surf wax to boards of club members and their visitors, would caddy the boards to water’s edge and retrieve the boards when they came in without a rider, before they hit the rocky beach.

“Dogny himself,” Warshaw pointed out, “gave a surf lesson to the queen of Denmark in the soft, rolling breakers outside the club, and the Peruvian president often hosted visiting dignitaries in the club dining room.”

“It’s built into the side of a cliff,” wrote Long Beach Surf Club president Jim Graham in 1965. “The entrance lobby is used to display surfboards and club trophies; the outside terrace has a bar, and a spacious, beautifully-kept pool surrounded by deck chairs and lounging pads.”

“Club Waikiki was remodeled in 1956 and again in 1962. The joining fee in the mid-‘60s was $25,000. More than just a surf society club, Club Waikiki was (and to a large degree remains) a power spot for those at the highest levels of Peruvian business, entertainment, and government.”

47

Al Dowden and Kon-Tiki, 1953

During the summers of 1952 and 1953, Club Waikiki was visited by California surfer Al Dowden, a member of the

San Onofre Surf Club. At that time, Peru was just beginning to become a favorite stop for more adventurous travelling surfers from Hawai‘i, California and Australia. Word was spreading about Club Waikiki and Peruvian surf. Dowden quickly found out that the surfboards then being used in Peru were 1930s and ‘40s era hollowboards better suited for paddling than for surfing. He extended an invitation to Eduardo Arena to visit California, and especially, to see check out the

balsa and fiberglass Malibu boards most all California surfers were riding. Eduardo Arena’s visit to California was postponed until June 1954, but after he brought a Malibu chip back to Peru, a dozen members of the Waikiki quickly commissioned their own balsa wood boards from

Hobie Alter.

48

“Al Dowden,” Felipe answered when I asked him if he knew the story of Dowden’s influence on Peruvian surfing. “I believe that he was a pilot for an airline company, at the time, called Panagra, and flying from Santiago, Chile to Lima. He flew over the ocean just south of Lima and, from the air, saw what looked like an excellent surfing spot. So, I guess he was a member or frequented Club Waikiki while he was in Lima. He got the club members excited with the story of the surfing spot he had seen from the air.

“They made a surfari down south to explore. They found Kon-tiki, they surfed it, and they had a very difficult time. They were not used to waves of that size. They later named the spot ‘Kon-Tiki’... They tried to paddle out straight through the waves like they did at Miraflores, in front of Club Waikiki, where the surf is smaller and you can paddle straight through it. At Kon-Tiki, the waves are big and you don’t paddle straight through the white water. They did not know that. And so, they got worked, beat up, and decided it was a very dangerous spot. You know, you could possibly drown there because it was a 3/4 of a mile paddle out from the beach.”

49

The Surf Report, Volume 13, Number 11, published in 1992, classifies Kon Tiki as “a big wave spot in the Punta Negra area, similar to Pico Alto. Lonely and distant, it breaks about ¾ of a mile offshore, with a range between 6 and 18 feet.”

50Kon-Tiki is an old name for the Viracocha, the great creator god in the pre-Inca and Inca mythology of the Andes region of South America. Viracocha was one of the most important deities in the Inca pantheon and seen as the creator of all things, or the substance from which all things are created, and intimately associated with the sea.

51 Viracocha created the universe, sun, moon and stars, time (by commanding the sun to move over the sky)

52 and civilization itself. Viracocha was worshipped both as god of the sun and god of storms.

53 He was represented as wearing the sun for a crown, with thunderbolts in his hands, and tears descending from his eyes as rain.

54According to the myth recorded by Juan de Betanzos,

55 Viracocha rose from Lake Titicaca (or, in some versions of the legend, the cave of Pacaritambo) during the time of darkness to bring forth light.

56 He made the sun, moon, and the stars, then he made mankind by breathing into stones. His first creations were brainless giants that displeased him, so he destroyed them with a flood and made new and better ones from smaller stones.

57 Viracocha eventually disappeared across the Pacific Ocean by walking on water, and never returned. Later, he wandered the earth disguised as a beggar, teaching his new creations the basics of civilization, as well as working numerous miracles. He wept when he saw the plight of the creatures he had created. It was thought that Viracocha would re-appear in times of trouble. Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa noted that during this time

incognito, Viracocha was described as ‘a man of medium height, white and dressed in a white robe like an alb secured round the waist, and that he carried a staff and a book in his hands.’”

58

George “Patillo” Downing & Kon Tiki, 1954

In summer 1954, Hawaiian surfer

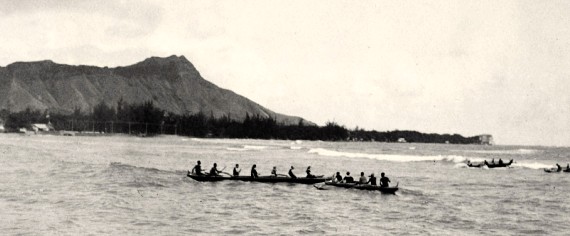

George Downing visited Peru for his first time. The “Waikikianos” – those surfers organized under the banner of the Waikiki Club – wanted to take their surfing to a higher level, so they sent a letter to the

Outrigger Canoe Club back in Waikiki, Hawai‘i, requesting them to send their best surfer to become a trainer of Peruvian surfers. Back then, George Downing had just won or was just about to win the Makaha International Surfing Championships, in November, and was elected unanimously by members of Outrigger to represent Hawaiians in Peru.

59The Makaha International Surfing Championships were held from 1954 to 1971, usually in November or December. It was regarded in the late 1950s and early 1960s as the unofficial world championships. The contest was the brain child of

Waikiki Surf Club founder, surfer, and restaurant supplier John Lind.

60Downing came to Peru with a lightweight balsa wood board covered with fiberglass, not a Malibu chip but more of a gun. He spent a lot of time in the water at Miraflores, earning him the affectionate nickname of “Patillo” partly by physical appearance and partly because, like those restless seabirds, Downing spent all day in the sea.

61Downing opened the eyes of the Waikikianos by going across the waves rather than in front of them. Also, his balsa board was a huge technological step forward. Not only was it light from the wood, but the addition of fiberglass and a fin were still novel concepts to the Peruvians in the mid-1950s who were still surfing on 1930s-style boards. After a while, Downing started asking about other beaches with bigger waves than Miraflores. The Waikiki Club members, of course, remembered Kon-Tiki, discovered by Al Dowden and Mark Nichols in the “rugged raid” summer 1953.

62The following day, Downing was standing on the edge of Kon Tiki. He entered the sea of Punta Hermosa that day and rode more than a dozen waves. The Waikikianos got totally stoked watching Downing ride the big surf of Kon Tiki on his balsa board; the same spot where a number of them had been repulsed just the summer before. Downing seemingly did what he wanted with his board, riding the highs and lows of the waves in an aggressive style. The Waikikianos had the impression that they were watching a sport completely different from the one they had been practicing.

63“When George Downing arrived in Peru,” Felipe Pomar told me, “he brought a balsa wood board with a fin and he showed the Peruvian surfers that the big waves could be surfed successfully and he was the first one to do it [in Peruvian waters].”

64

“George Downing went to Peru many times,” afterwards, Felipe continued. “He is greatly respected there. Peruvian surfers love George Downing. He was the first person that showed Peruvians how to successfully ride big waves and, for some reason, Peruvians really valued big wave riding thereafter.”

Back on shore with his two inseparable companions – Pitti Block and Eduardo Arena – William “Pancho” Wiese waited for Downing to come in, then borrowed his board. “Lit by the last rays of the sun, Pancho went to sea, ready to conquer once and for all the huge waves that would become legend.” As he lay on the board, “Pancho was keenly aware of the lightness of it and almost without realizing it, paddled through the breakers of Kon Tiki after many strokes. Once outside, he judged the best take-off spot and waited. Back on the shore, Pitti Block and Eduardo Arena watched their friend, not sure exactly what would happen. Soon Pancho paddled for a wave, stood at the most critical point of the ridge and descended rapidly, standing on the light balsa wood surfboard, on a wave three meters high. By all accounts, Pancho rode the wave masterfully, riding for five hundred feet of’ ‘pure dynamite,’ before making it to the beach with a big smile. From that point on, Pancho became a lover of big waves, and he vowed that someday he would dominate the outside reef of Kon Tiki.”

Pancho’s first ride at Kon Tiki made for one of the greatest days in his life. It set the stage for him to become one of Peru’s most experienced big wave riders. Some days later, just before George Downing returned to Hawai‘i, Pancho paid 120 gold sols for his surfboard – which was a pretty hefty sum back then. A few months later, Pancho was invited to participate in the Makaha International Surfing Championships International, becoming the first surfer to represent Peru in an event of international standing. With his experience in riding the waves of Kon Tiki just beginning, Pancho Wiese still came in fifth place.

George Downing won it.

Soon after the Makaha championship, Eduardo Arena brought a number of balsa boards in from California. The heavy cedar planks the Peruvians had been using were subsequently sent “to the attic of memories.”

George Downing’s contributions were not limited to just a technological advance in surfboards and demonstrating angling across a wave face rather than riding straight in. The Hawaiian also taught the Waikikianos about training and the basics of contest organizing. The Waikikianos learned of the extensive endurance rowing, relay races and sprints that took place along the Hawaiian coast as integral elements in surf contests. Significantly for world surfing, Downing outlined how contests were organized so that the Peruvians had something to go by in organizing the First Peruvian National Championship, in 1955.

66

Los Tres Mosqueteros and Kon Tiki

The discovery of Kon Tiki, as Peru’s first big wave spot, changed Peruvian surfing forever. Peruvian surfers were predisposed to treat riding the biggest wave as the true test of a surfer. Once they saw that they had world-class big waves in Punta Hermosa, that they could actually ride, big wave riding became the focus of all the top Peruvuan surfers. A trio of friends, in particular, became obsessed with the idea of dominating those waves: William “Pancho” Wiese, Eduardo Arena and Federico “Pitti” Block. They became the first of Peru’s most remarkable generation of surfers: Ola Grande Corridors. They called themselves Los Tres Mosqueteros, after the unforgettable characters – The Three Musketeers – created by Alexandre Dumas. They made a pact with each other to rule the waves of Kon Tiki.

Gradually, the habit of going to Kon Tiki spread among the other members of Club Waikiki, as well. Toward that end, they brought a part of Club Waikiki along with them. Lead by the patriarch Carlos Dogny,

Los Waikikianos went on the weekend to Punta Hermosa to try their skill in the waves of Kon Tiki. Photographs from that era show the surfers sitting comfortably in elegant tables set on the sand, served by waiters dressed in impeccably clean pressed white uniforms, with clean linens, glasses, cutlery and napkins. The Waikikianos feasted on succulent banquets, warm sea breezes, the sound of distant crashing waves, and the opportunities to ride them. It was a far cry from the surf safari’s most other surfers took in places like the United States, Hawai‘i, South Africa and Australia. These forays of the Club Waikiki members to Kon Tiki took place more and more frequently as time went on. An added plus was that the beaches of Punta Hermosa – unlike Miraflores, covered with stones and full of sea urchins – had plenty of sand where blankets could be spread and children could play without harm, while surfers contemplated the surf and reveled in the riding of it. From the outset,

Los Tres Mosqueteros became the top surfers of Kon Tiki.

67

In a magazine published by the Club Waikiki in 1967, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the founding of the club, Charles King and Fernandini Lama wrote about the first sessions at Kon Tiki, when they were still using the 1940s Blake-style hollow boards:

“You have to consider what these first forays into the open sea were like. The noise produced by the rumblings of the big waves inspired respect, along with the wind and mass of water that brought each of these waves. Despite our surfboards being sturdy, we all had to keep in mind the possibility of their destruction on the rocks if we lost them. Most important was ensuring the health of the ‘peg’ as it is called in nautical terms – the bronze cap located at the stern and near the ‘eye bolt’, the bronze handle each board featured. The stopper served to drain the water that inevitably crept in after a few moments use. The handle was used to hold the board with both hands, using all the weight of your body to keep the sea from sweeping it away, as often happened.”

After the first big wave season at Kon Tiki, the Waikikianos decided to make a further land acquisition south of the club. Following a general meeting held on June 12, 1955, and buying of the land, construction of the first facilities at Kon Tiki was begun, essentially serving as an annex of Club Waikiki. In this way, the club extended its rule to the beaches south of Lima, allowing surfers access to larger and stronger waves. With the acquisition of the premises at Kon Tiki, the Waikikianos now had a venue in which to hold the first national and international tournaments.

68

First Peruvian National Championship, March 1955

Peru was now poised to develop both national and international championships. The first surfing tournaments followed the rules and events passed on by George Downing. These included, in addition to tests of skill on the waves, a series of competitions designed to measure strength, endurance and ability. The champion of any given contest was determined by the amount of points accumulated in the different tests.

The First Peruvian National Surfing Championship was held on Sunday, March 27, 1955, at Kon Tiki. The beach was covered by a dense fog as the white foam of the bay rumbled onshore. Suspicious of the huge rumbling coming from the unseen breakers, competitors crossed themselves before entering the water. The surfers that day included Eduardo Arena, Alfredo “Pecho” Granda, Guillermo “Pancho” Wiese and Federico “Pitti” Block. The judges were Alfredo Alvarez Calderon, Richard and Charles King, and Fernandini “Rex” Lama – all three of whom paddled out with the competitors.

“Charles King was a great Lord,” Felipe Pomar declared. “A lover of

la tabla, he was one of the first Peruvians who traveled to Hawaii for surfing during the era of Duke Kahanamoku. His daughter Mannie King was one of the great surfers of the ‘60s. ‘Rex’ always supported and participated with great care in all Club Waikiki activities. This included Big Wave Championships, International Championships, World Cup ‘65, luau’s, and so on. He was several times President of the Club Waikiki. He was affectionate, friendly, kind and a great friend.”

69

Such was the respect that the noise of the sea inspired, and because they could not see the exact size of the surf due to the fog and distance, competing surfers decided to go out with life jackets that day.

No wave was below seven meters high (23 feet), and although most of the surfers were already familiar with the waves of Kon Tiki, this was by far the biggest surf they’d ever been in. Charles King and Rex Lama described the scene:

“When the fog cleared a bit, we took off seaward on our boards, looking for the ‘calm channel’ we had used before, to get out, but on this occasion had completely disappeared. [Later,] The competitors had difficulty finding take-off spots, frequently changing their positions…”

70Struggling against the waves on the paddle out, both surfers and judges finally arrived in the area a little past where the waves were breaking. The first to catch a wave was Alfredo “Pecho” Granda, who, unlike his rivals who were on fiberglassed balsa boards, rode an old-style 1940s type board. Encouraged by Pecho, the young “Pitti” Block took off second, followed by Eduardo Arena and “Pancho” Wiese. Observing the surfers, judges used three criteria to score the rides: wave size, degree of difficulty, and distance traveled. After a while, it looked like William “Pancho” Wiese would win the competition, not only due to his riding of Kon Tiki, but also the points he had amassed in the other events. However, it was “Pecho” Granda who scored the biggest wave of the morning, riding for more than an estimated one hundred and fifty meters, and pushing his total points beyond those of Pancho. That day marked the beginning of big wave championships in Peru.

71“Pecho” won the contest and thus became the first national champion surfer of Peru. “Alfredo Granda’s nickname was ‘Pecho’ (chest),” Felipe explained. “Alfredo was a tall, good-looking, athletic man who also had a big chest.”

72After the celebrations and awards ceremonies, it was decided that the life jackets had made the contest more dangerous than it otherwise would have been and their use was ruled out from that point forward. Ultimately, the national championships would serve as the training ground for Peru to forge its first world champions.

73The big wave riding event was not the only determination of the winner. Points were totaled from all events, including the paddle between La Herradura and Club Waikiki, a distance of about ten kilometers (six miles) and short distance paddling speed tests of 2000, 1000, 500 and 300 meters. There were also events for women and and tandem sessions. But, the highlight of the championships, reserved for last, was the big wave event at Kon Tiki. There, surfers were judged in four aspects: size of the wave, position on the critical point of the wave, and speed and distance traveled. Winning the final big wave event did not guarantee a surfer would win the overall championship. Rather, the winner was determined by the accumulation of points earned in all events. In short, the winner had to be a comprehensive aquatic athlete. This aspect of the surfing competition was not lost on the media. At least one newspaper of the time declared that “in Waikiki there are more races than in the hippodrome.”

74In ancient Greece, a hippodrome was a stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. Some present-day horse racing tracks are even called hippodromes. The Greek hippodrome corresponded to the Roman Circus, except that in the latter only four chariots ran at a time, whereas ten or more contended in the Greek games, so that the width was far greater, being about 400 feet (120 meters), the course being 600 to 700 feet (210 meters) long. The hippodrome was distinct from a Roman ampitheatre which was used for spectator sports, games and displays, or a Greek or Roman semi-circular theater used for theatrical performances.

75The Greek hippodrome was usually set out on the slope of a hill, and the ground taken from one side served to form the embankment on the other side. One end of the hippodrome was semicircular, and the other end square with an extensive portico, in front of which, at a lower level, were the stalls for the horses and chariots. At both ends of the hippodrome there were posts (termai) that the chariots turned around. This was the most dangerous part of the track, and the Greeks put an altar to Taraxippus (disturber of horses) there to show the spot where many chariots wrecked.

76Although all events of the Peruvian championships helped determine the winner, it was the big wave event that was scored the highest. “Peruvians always gave more weight to the big wave riding,” confirmed Felipe Pomar, “so the main contest in Peru was always the big wave event.”

77

First Peruvian International Championship, 1956

Carlos Dogny went back to Hawai‘i in 1955 and competed in the Makaha Championship in November/December. While there, he was particularly struck with the image of women surfing in competition. In Peru, up to that point, surfing had been pretty much a man’s game. Dogny thereupon invited the female members of the Hawaiian

Waikiki Surf Club to attend the forthcoming Peruvian meet only months away. Following that, he then extended an invitation to the club as a whole, to send a team to compete in what was first known as the “South American Championships”.

78 Although the Hawaiians did not participate in numbers, in Peru, until 1957, once they did, for years afterwards, there was a back and forth exchange of Hawaiian and Peruvian surfers riding together in each other’s country. This cross-pollination peaked in the mid-1960s.

The Peruvian International Championships – later “renamed Peru International”

79– were held from 1956 to 1974, usually in February or March. For many, it became “one of the sport’s biggest and most prestigious events,” wrote Matt Warshaw. “The Peru International Surfing Championships were conceived, developed, and underwritten by Club Waikiki… and directed by club member Carlos Rey y Lama.”

80“Carlos Rey was a great gentleman,” Felipe Pomar said of Carlos “Rex” Rey y Lama. “He was very involved with Club Waikiki. He was president of the club on, possibly, more than one occasion. He visited Hawaii. He met

Duke Kahanamoku and he was very influential in organizing a lot of the internaional events and… judging many of the international competitions.”

81

“The 1956 debut event,” continued Matt Warshaw, “was little more than a friendly scrimmage between Club Waikiki and the San Onofre Surfing Club of California; it was held at Kon-Tiki, and won by future International Surfing Federation president Eduardo Arena. For the 1957 event, the Peruvians competed against a team of Hawaiian surfers. A small group of Californians attended the third edition of the contest in 1961, won by

Surfer magazine founder

John Severson.”

82

The San Onofre Surf Club participants included: Albert Dowden, Tom Wilson, Richard De Witt, Robert Silver, Reinz Wundelick. The Peruvian team consisted of: Eduardo Arena, Augusto Felipe Wiese, Fernando Arrarte, Federico Block, Felipe de Osma, Ramón Raguz, Rafael Navarro, Alfredo Granda, Richard Fernandini, Herbert Mulanovich, Alfredo Hohaguen, Guillermo Wiese, Armando Vignati, and Dennis Gonzáles.

Al Dowden, president of the San Onofre Surf Club, accumulated the most points winning in the combined tests, but in the waves of Kon Tiki, Eduardo Arena dominated the competition. Because the big wave event is valued so highly by Peruvians, Arena is considered Peru’s first International Champion. He joined a very short list that included George Downing, who had won the first international championship held at Makaha in 1954.

Like the national championships, the international was divided into different trials, through which the participants piled up their points. The 1000 meter paddling race was won by Eduardo Arena. The 2000 meter race was won by Dowden. The tandem competition was won by Felipe Augusto Wiese carrying on his shoulders the beautiful Karla Eberl. The rowing event from La Herradura to Club Waikiki was won by Dowden.

83

Overall Results:

1.Albert Dowden (USA), 32 points

2.Eduardo Arena, 20 points

3.Augusto Felipe Wiese, 8 points

4.Fernando Arrarte, 8 points

5.Federico Block, 8 points

6.Robert Silver (USA), 4 points

7.Federico de Osma, 3 points

8.Ramón Raguz, 2 points

9.Rafael Navarro, 2 points

10.Alfredo Granda, 1 point

84

Results of surfing at Kon Tiki:

1.Eduardo Arena, 14 points

2.Albert Dowden, 11 points

3.Pitti Block, 8 points

85

Second Peruvian International, 1957

Peru held its Second International in 1957, attended for the first time by a team of Hawaiians including Conrad Cunha, Robert “Rabbit” Kekai, Ethel Kukea and Roy Ichinose. Conrad Cunha won the Big Wave Competition held in Kon Tiki, Rabbit Kekai dominated the rowing between La Herradura and Waikiki, and Eduardo Arena won the 1000 meters race.

86“… by the end of the decade,” wrote Matt Warshaw, “the renamed Peru International was second in surf world prestige only to the Makaha International. The contest ran continuously until 1974.”

87The Peruvian team consisted of Eduardo Arena, Dennis Gonzáles, Héctor Velarde, Augusto Felipe Wiese, Guillermo Wiese, Federico Block, Fernando Arrarte, Alfredo Hohaguen, Oscar Berckemeyer. The Hawaiian team comprised

Rabbit Kekai, Conrad Cunha, Robert Ichinose and

Ethel Kukea.

88

Results:

1. Conrad Cunha, 12 points

2. Guillermo Wiese, 8 points

3. Federico Block, 6 points

4. Rabbit Kekai, 4 points

5. Eduardo Arena, 4 points

6. Augusto Felipe Wiese, 4 points

89

Felipe Pomar (1943- )

It was during this period, beginning in 1957, that Felipe Pomar, aged 14, began his life as a surfer.“Debonair regularfoot surfer from Lima, Peru; winner of the 1965 World Surfing Championships, and one of the 1960’s most dependable big-wave performers,” wrote Matt Warshaw, “Pomar… won the Peru International in 1962, 1965, and 1966 (placing second in 1963 and 1967), was a four-time finalist in the

Duke Kahanamoku Invitational between 1965 and 1969, and finished second in the 1970 Smirnoff Pro. All of these events were held in oversize surf.”

90 Felipe Pomar was born in Lima, Peru’s capitol city, on November 24, 1943. His parents were Don Felipe and Dona Carmela Pomar Tenaud Quimper Rospigliosi.

91

“We lived in Lima, in a place called San Ysidro,” Felipe told me. “My grandfather had come from Europe and purchased some plantations a couple of hours outside of Lima. My dad loved sports. He played polo, raced cars and he liked big game hunting. He went to Africa, you know, on the big game hunt, and came back with stuffed lions and leopards and elephants and buffaloes, great kudus, and all kinds of stuff.

“My dad took me hunting on a couple of occassions... but I didn’t enjoy it. I enjoyed a little tennis and played a lot of badminton and the swimming.”

92“During the summertime, I would go to my dad’s hacienda and ride horses. I had my favorite horse which I was the only one who rode him. During the school year, nobody would ride him and when I would come back in the summertime, I’d get on him and he would always throw me off because I wouldn’t let anybody else ride him.”

93

“I first went to an American school called Franklin Delano Roosevelt and from there I was transferred to a British school called Markham College.

“My life was kind of boring until I started surfing. I used to do competitive swimming. I disliked the rigorous training. We were forever swimming from one end of the pool to the other. So, when I found surfing, it was practically love at first sight. I had excitement, fun and exercise, but it didn’t feel like work.”

94In 1957, Pitti Block introduced Felipe to Club Waikiki and surfing.

95“After a slow start I fell in love with surfing,” Felipe recalled. “I loved the fun, freedom and excitement it offered in contrast to the tidious long workouts and discipline required for competitive swimming.”

96

“Pitti [Pee-tee] was a friend of my family. When I was young – maybe 13 or 14, he used to come and visit us. The story I heard was that every time he visited my family’s home and he wanted to use the phone, the line was busy because I was on the phone talking to my girlfriend. So, Pitti decided that it would be good for me to get involved in something that got me out of the house.

“So, he took me to Club Waikiki, leant me a surfboard, and basically got me into surfing. He also shaped my first surfboard and he is – to this day – one of my best friends.”

97

“My earliest memories of Club Waikiki,” Felipe told me wistfully, “... it was a wonderful place for a young surfer – a young, impressionable surfer. I got to meet all these older guys who were wealthy, successful, interesting. There was Carlos Dogny, the founder of the club. There were the Peruvian national big wave champions and they were all there. I got to meet them and they became my friends and I got to hang out and surf with them. And, so to me, that was a wonderful time [in my life] and I totally loved the Club Waikiki and the members and the surf.”

“When Pitti took me to learn surfing at the Club Waikiki, I met Joaquin Miro Quesada, who was about my age. We both wanted to learn to surf and surfed at every opportunity. Pitti built my first balsa wood surfboard in his factory. Shortly afterwards, I met Pancho Wiesse, who was married to Pina Miro Quesada, Joaquin’s sister. Pancho was the first big wave surfer at Kon Tiki. Joaquin and I loved both Pitti and Pancho and always tried to convince Pancho to go to Kon Tiki. Pancho was at that time the National Champion big wave surfer, so it was never very hard to talk him into it. Sooner or later we all would be heading towards Kon Tiki. At that time, there was never anyone else in the water. Other champions of the Ola Grande at the time were Pitti Block, Eduardo Arena, Dennis Gonzales and Alfredo ‘Chest’ Granda.”

“Pancho Wiese [Vee-see] was a great sportsman,” Felipe Pomar attested. “He was both a national squash champion and a national big wave champion.

“Pancho mentored myself and Joaquin Miro Quesada. We were the two young, up-and-coming surfers who also loved big waves and Pancho was the guy who took us down there [Kon-Tiki] to surf.”

100“My surfing buddy, Joaquin Miro Quesada and I were the youngsters among other Club Waikiki members. We were the first club members to surf through the cold Lima winter, before wetsuits. We would run up and down stairs, and do high-intensity exercises to get as hot as possible. Then we’d go surfing and see how long we could last in the cold ocean water.”

101“Joaquin and I started surfing almost every day. When summer ended, the other surfers normally quit surfing until the following summer. Joaquin and I were still entering the sea in winter, without wetsuits, because at that time they were unknown. We did lots of exercise, ran to get very hot and sweaty so we could last out in the cold water as long as possible. I remember being in the water, so cold and blue when Joaquin told me: ‘Imagine you’re in the Sahara, dying of heat.’ Running waves all year and doing much exercise, apart from surfing, kept us in excellent shape. That, plus a passion for surfing allowed us to both excel, as Joaquin also won many championships and became National Champion.

102

When asked who motivated him when he was starting out, Felipe Pomar replied:

“Definitely Pitti Block, who taught me how to surf. Sources of inspiration were Joaquin Miro Quesada, Pancho Wiese, Pocho Caballero, the unforgettable Carlos Dogny and Eduardo Arena, who organized the best world championships ever.”

“My great friend Pitti Block took me to the Waikiki club when I was about 14 years old. The members were all surfers and a group of really admirable people. I was fortunate to meet and establish friendship with Carlos Dogny, Pancho Wiese, Eduardo Arena, Carlos Rey y Lama, ‘Kichi’ Mulanovich, ‘Pocho’ Knight and many more friends.”

Of the surfers of his own generation, notable were Joaquin “Shigi” Miro Quesada, Miguel Plaza, and Héctor Velarde.

“Joaquin ‘Shigi’ Miro Quesada had a real passion for surfing. By his love and dedication to surfing, he deserved to be world champion. ‘Shigi’ was a great lover of surfing and should be remembered as a great surfer, and National Champion, who was promoted to the next generation. ‘Shigi’ risked his life on a grand adventure in the North Shore of Hawaii. Unfortunately luck did not accompany him. ‘Shigi’ died running waves at Pipeline, one of the most difficult and dangerous waves of Hawaii. He died at an early age, and therefore we will never know what more he could have achieved in his life. Joaquin died in his prime, running waves in the most dangerous place in Hawaii, Pipeline. I miss him a lot because he was like my brother. Joaquin ‘Shigi’ Miro Quesada deserves to be remembered for his valuable contribution to our sport. In my opinion, there should be a memorial event with his name.

103In

1959, Peru’s national big wave champion “Pancho Wiesse took us [Shigi and I] under his wing,” continued Felipe. “Pancho would drive us to Kon Tiki, Peru’s big wave spot, and we had amazing fun and great adventures. Ninety-nine percent of the time we were the only surfers in the water. Joaquin and I discovered many of [what are now] Peru’s most popular surfing spots.”

104“I liked to surf Kon Tiki the most. It was so exciting, each session was an adventure. I also liked the Pampilla, because it was so much fun. Joaquin and I were the first to surf there. For a time, it was like our secret beach. I also liked Triangle, because it was a very clean and perfect wave.”

105

“My generation learned to surf Ola Grande from Pancho Wiese, Eduardo Arena, Dennis Gonzales, Pitti Block and ‘Pecho’ Granda. They were the Champions of Kon Tiki and taught us how to ‘run the blue.’

“Miguel Plaza I knew very little during my years in Peru. It was only after being in Hawaii that I got to know him better. Miguel has had a long and successful career… in international competition.”

“The best surfers in my generation were the brothers Velarde, Carlos and Hector.

“Hector Velarde was my teacher for several years; a great athlete, great surfer, great athlete, great champion like his brother Carlos Velarde.

“Hector and Carlos were studying in the United States between the years 1958 to 1961. Joaquin and I were young surfers who were winning most of the competitions in their absence. They were a few years older and had more experience. They had already surfed in Hawaii. In addition, both had impressive physiques and, in my opinion, were the best surfers in Peru at that time. Joaquin and I were like 17 or 18 when they returned to Peru, and immediately we became friends. I admired the skill of both and learned a lot from them, besides sharing fond memories and beautiful moments.”

“Between 1961 and 1963,” Felipe continued, “Héctor Velarde – in my opinion – was the most comprehensive and experienced surfer in Peru. We were like brothers: Carlos, Hector Joaquin and me. Hector was my older brother and possibly the person who most influenced my decisions at that time. Joaquin was like my younger brother and Carlos and Hector my older brothers Carlos. Carlos was already working at the time. The three of us were dedicated to the surfing. Hector became our ‘Kahuna,’ and Joaquin and I were like his disciples.

“There are many great surfers who stood out in my time. Unfortunately, I can not give all the respect they deserve. They know who they are. Those I must mention are: Pitti Block, for introducing me to surfing and giving me his friendship; to Pancho Wiese, for sharing his great surfing; to Eduardo Arena, by his example and support; Los Lobos brothers, by the beautiful times we shared; to Rafael ‘Mota’ Navarro, ‘Pocho’ Caballero, Raul Risso and many of the friends with whom I shared memorable days and waves.”

“Gordo Barreda I knew slightly because of our age difference. After I left Peru for Hawaii… I met [his] mom, Sonia Barreda… Gordo surfed very, very well, and had a nice style. At one time, the Barreda brothers were the best surfers in Peru.”

106

1959

Thanks to the contact established with Hawaiian surfers from the Second International Championship, a Peruvian delegation traveled to Hawaii in 1959. Invited by the

Outrigger Canoe Club in Honolulu, Carlos Rey y Lama, Richard Fernandini, Federico “Pitti” Block and Fernando Arrarte were lucky to represent Peru in Hawai‘i.

Travelling with the Peruvian team were Cesar Barrios, Carlos Aramburu, Rosalba Daly King and Cecilia Tudela de Aramburu. On Sunday, July 12, 1959, the board competitions were held on the beach at Waikiki. The Peruvian team faced the best surfers in the world and a large crowd of Hawaiian spectators. The Peruvians put in a respectable showing in the competition organized by John Lynn and endorsed by Duke Kahanamoku.

107

One of the most memorable moments at Club Waikiki occurred in 1959. According to an account in the newspaper

El Comercio, about 12:45 p.m., Richard Payet Fernandini spotted a squadron of planes flying over the ocean, north to south off the coast of Miraflores. From the direction they were flying, Fernandini was sure they would soon disappear behind the hills of Chorrillos, when suddenly one of the planes appeared to drop a device in the water. The plane consequently lost altitude. Facing the Club Waikiki, the military plane flew to a height of a hundred meters, across from the Quebrada de Armendariz, practically at sea level. Fernandini and his friends first thought it was a reckless aerobatic maneuver by the pilot, but then they saw the plane hit the water, bounce on the surface and quickly sink. Fernandini, “Pitti” Block, and two other Waikikianos jumped into a car with their boards loaded, and drove as close to the downed plane as possible. Running into the water, they paddled as fast as they could to cover the thousand meters separating the plane from the shore. They were able to reach the pilot in time to save his life, initially finding him floating unconscious, face up. They laid him on top of three of the boards, on his back, and swam in shifts until they reached the beach.

108

Another landmark event not only in Peruvian surf history, but French, too, occurred in October 1959. On one of his many trips to the land of his ancestors, Carlos Dogny Larco took his board to France and gave a demonstration on the waves of the French resort at Biarritz. Vacationers were surprised to see a man surfing off the beach in front of them and younger people were quick to show interest. As a result of, Dogny helped establish an extension of Club Waikiki at Biarritz, named “Club Makaha.” Over time, French surfers would give high importance to international events, many of them participating in world championships organized by the International Surfing Federation.

109

The 1960s

Peruvian surfing in the 1960s amounted to the emergence of the country and its surfers squarely upon the international surfing scene.