The human act of riding ocean waves on floatation devices has been going on for

thousands of years. We, in fact, do not know how many thousands of years. It has been reasonably estimated that the act involving wooden boards could date as far back as 2000 B.C. (4000 B.P.), before the beginning of the Polynesian migration across the

Pacific Ocean.

If we count canoe surfing, the act must be far older than that and if we include bodysurfing, then we must consider the span of time in terms of tens of thousands of years.

Surfing on boards –

he’e nalu– rose to a high level of development in the Hawaiian Islands sometime after

Polynesians first settledthe Hawaiian chain beginning around 300 A.D. (2300 B.P.). “Wave sliding” using boards – along with canoe and body surfing – not only became important parts of the lifestyle of all Hawaiians prior to European contact in the later 1700s, but was also integrally connected with Hawaiian culture.

In stark contrast to this “golden age,” surfing fell to an almost ignominious near-death during the 1800s – mostly due to European and American cultural, political and religious influences.

During “The Revival” period of surfing at the very beginning of the Twentieth Century, surfing’s decline was arrested and set back on a course of natural evolution. Since that time, surfing has grown vastly in popularity and now is practiced in most every corner of the world. Key figures in this resurgent interest in surfing include:

George Freeth,

Alexander Hume Ford, Jack London,

Duke Paoa Kahanamoku,

DadCenter, Dudie Miller, “John D” Kaupiko and numerous beach boys and surfing

wahines at

Waikiki, on O’ahu, in the first two decades of the 1900s.

A little surprisingly to those of us looking back at it now, surfing’s growth was not explosive following its resurgence, but rather a slow and gradual progression. For this reason, the surfing years between 1912 and 1928 are not well known and, predictably not well documented.

We, of course, know the historical context. The

1910s were dominated by events that would lead to the First World War. The war, itself, was vastly different than any other war that had preceded it. “The total number of casualties, including killed, wounded, and missing, is figured at 37.5 million… An outbreak of influenza in the autumn of 1918 compounded the death toll as it swept through populations already weakened by the nutritional privations of total war.”

In Europe and other nations that had been caught up in the global struggle, “Wartime disruption helped cause a sharp recession in 1920-21… For most nations, prosperity returned only in the mid-1920s.”

“The catastrophic toll of the war also resulted in a new, looser code of morality, especially in a growing urban environment. A new generation, decimated by war, felt betrayed by their elders and rejected the more austere standards of conduct they had been taught as children.”

To truly appreciate the great surfing decade that the 1930s was, it is important to understand this time leading into it, in the Earth zones where surfers were riding waves in the Hawaiian style: Australia, Southern California and – of course – Waikiki.

Australia, 1910-1930

It is still a common misconception that surfing in Australia began in 1914-15, with the visit of

Duke Kahanamoku to New South Wales and the surfing demonstrations he gave at that time. In fact,

Australia’s surfing roots go much further back – as far as the late 1800s, before legal rights to swim in the open sea had even been won.

This was because “In Australia,” emphasized the Australian authors of

Surfing Subcultures, “the origins of surfing were based on body surfing rather than on traditional board riding... the early Australian settlers – mainly of English origin – found no native surfing tradition to encourage or restrict either body or craft-based surfing, as was the case in

Hawaii.”

Australian surfing’s Polynesian connection came in the form of Alick Wickham and Tommy Tana. In the 1890s, Alick Wickham, a native of the

Solomon Islands, became an important influence on Australian swimming when he demonstrated a “crawl” stroke that was later exported to the rest of the world as the “Australian crawl.”

Around the same time another South Sea Islander, Tommy Tana – a youth employed as a houseboy in the Manly district – was body surfing at the beach there. Tana hailed from the Pacific

islandof

Tana, in the New Hebrides, which is now called by its traditional name of

Vanuatu. He amazed onlookers at

ManlyBeachand inspired others to dive in. His style was studied and copied by Manly swimmers like Eric Moore, Arthur Lowe and Freddie Williams. Williams soon became the first local considered to fully master bodysurfing. Later on, Freddie Williams became a public figure when he made the first publicized rescue of another swimmer at

ManlyBeach.

After the turn of the century, Alick Wickham shaped the first surfboard in

Australia. Hand carved from a large piece of driftwood found on Curl Curl beach, this board was so bad it actually sank.

Wickham’s knowledge of stand-up surfing using a board was obviously limited and is a testimony of how far surfing had fallen in such Polynesian locales as the

Solomon Islandsby the late 1800s.

When more novice swimmers and non-swimmers started ocean bathing off unsupervised beaches, accidents became numerous and soon raised hell with the public.

At

ManlyBeachalone, there were 16 drownings in the space of 10 years. Local government authorities and regulars at the beaches eventually figured out that the general public would need to be either regulated or monitored. This realization became the driving force for the formation of the Australian Surf Life Saving movement.

By 1909, the newly formed Australian Surf Life Saving Association published that there were eleven clubs active in

New South Wales. According to the report, no lives had been lost in the previous twelve months while beach patrols had been operating. Thereafter, similar reports were made with similar statistics even though “surf bathing” and surfing grew at a dramatic rate across the beaches of

Australia. By 1964, there would be 112 clubs operating in

New South Wales alone.

The first Surf Carnival was held on January 25th 1908 at

ManlyBeach. Six clubs competed and the first surfboat race, with various craft, was won by Little Coogee (now Clovelly), using their whale boat. Surf Carnivals quickly become a popular method of revenue for the Live Saving Clubs. The revenue from gate receipts were used to purchase gear and improve facilities.

Tamarama Carnival, alone, attracted fifteen thousand spectators in February 1908.

That same year,

Alexander Hume Ford– the man who more than anyone helped publicize surfing at

Waikikiduring the first two decades of the Twentieth Century – visited Manly. He wrote, curiously, that “I wanted to try riding the waves on a surf-board, but it is forbidden.”

Many writers – including myself, once upon a time – have written that before Duke Kahanamoku came to Australia and became the first one to really popularize the sport, there were no surfers riding surfboards. The historical record proves that this is not correct.

While assisting with the 1908 trade agreements between

Hawai’i,

Australiaand

New Zealand, Alexander Hume Ford introduced surfing to Australian Percy Hunter, the head of the New South Wales Immigration and Tourism Bureau. Two years later, when Ford visited

Australia again in 1910, he noted that there were already several surfboards stashed at

ManlyBeach.

This was a full four and a half years before

Duke Kahanamoku visited

Australiafor the first time and got credited for stoking Australians on stand-up surfing.

During this time, amongst some surf lifesavers, there was an understanding of what surfboards were. It was noted that “Fred Notting painted a brace of slabs and named them Honolulu Queen and Fiji Flyer; gay they were to look at but they were not surfboards.”

In 1912, well-known Australian swimmer, local businessman and politician

Charles D. Paterson, of

ManlyBeach,

Sydney, brought a solid, heavy redwood board back with him from

Hawai’i. He and some local bodysurfers tried to ride it, but with little success. “When he and his mates couldn’t figure out how to ride it,” Duke biographer Sandra Hall wrote, “his wife used it as an ironing board.”

Yet, Patterson and his mates were not the only ones who had attempted surfboard riding or were surfing prior to Duke’s visit. Early in 1912, the

Daily Telegraph reported on the second Freshwater Life Saving Carnival held on January 26th. In the account of the day’s events, there is mention of surfboard riding: “A clever exhibition of surf board shooting was given by Mr. Walker, of the Manly Seagulls Surf Club. With his Hawaiian surf board he drew much applause for his clever feats, coming in on the breaker standing balanced on his feet or his head.”

Whether the board

Walkerrode on was a knock-off of Patterson’s, Patterson’s, or an entirely separate board is unknown.

We do know for sure that following the arrival of C.D. Paterson’s board at Manly in 1912, a small group – the Walker Brothers, Steve McKelvey, Jack Reynolds, Fred Notting, Basil Kirke,

Jack Reynolds, Norman Roberts, Geoff Wyld, Tom Walker, Claude West (then aged 13) and Miss Esma Amor – all attempted surf riding on replica boards. Some of these tried surfing before and some after Duke’s visit. Made from Californian redwood by Les Hinds, a local builder from

North Steyne, they were 8 ft long, 20” wide, 11/2” thick and weighed 35 pounds. Riding the boards was limited to launching onto broken waves from a standing position and riding white water straight in, either prone or kneeling. Standing rides on the board for up to 50 yards/meters were considered outstanding.

In

Queensland, by 1913-14, prone boards four to five feet long, one inch thick, and about a foot wide were in use on Coolangatta Beaches.

These were made from slabs of cedar or pine and probably used as bodyboards.

Charlie Faukner read of Duke Kahanamoku’s surf riding and used a board as an aqua planner on the

TweedRiver, to ride at Greenmount in 1914.

Sometime slightly before 1914, at Deewhy, “Long Harry” Taylor “made a board resembling an old-fashioned church door, but his efforts in the surf were so futile they became ridiculous.”

So, yes, surfing on wooden boards – or their facsimile – had already begun by the time Duke Kahanamoku first visited

Australia in 1914-15. Even so, it is undeniable that it was Duke’s shaping his own board and then riding it at Freshwater that really got surfing going in

Australia. His riding was widely publicized and resulted in huge enthusiasm for stand-up surfing in

New South Wales. Unfortunately, this stoke was rapidly dampened by the onset of World War I, when many young Australians lost their lives on the battlefields of Europe, including Manly captain and Olympic swimming champion, Cecil Healy. Surfing, like most other Australian recreational activities, was largely put on hold until after 1918.

Duke Kahanamoku’s tandem partner while in

Australia, Isabel Letham, continued board riding at Freshwater up to 1918 when she moved to the

USA to work as a professional swimming instructor.

Other prominent boardriders in the Manly area, post-Duke, were Steve Dowling, “Busty” Walker, Geoff Wyld, Ossie Downing, Reg Vaughn (Manly), Tom Walker (Seagulls), Barton Ronald, Billy Hill and Lyal Pidcock.

Circa 1915, seventeen year old Grace Wootton (nee Smith) was encouraged to try prone boarding – body boarding – at

Point Lonsdale, Victoria. Using a board brought to

Australiaby “a Mr. Jackson and a Mr. Goldie from

Hawaii,” and after some basic instruction, Grace Wootton became a proficient and stoked surfer. A local carpenter was commissioned to make a board for her, for the following season. This board was solid timber, approximately 6 feet x 16 inches and a little over 1-inch thick. The cost of 12 shillings included her initials (GW) carved at one end. Photographs of Grace Wootton taken in 1916 show her surfing and her personally modified woolen swimsuit, purchased from Ball and Welch (Outfitters), Melbourne.

Following Duke’s surfing demonstrations in

Australia and

New Zealand, many boards were made in Oceana based on his handcrafted design.

Circa 1915, Collaroy Surf Life Saving Club member, Alf “Weary” Lee saw Duke Kahanamoku’s Dee Why demonstration and built his own board according to Duke’s design. Since the board was stored in the club house, it was available for younger club members to have a go of it.

Duke’s most stoked pupil, Claude West, was initially at the Freshwater Club but later moved to Manly. He became

Australia’s top boardrider for the next 10 years. Starting out riding Duke’s original pine board, West really got into stand-up surfing and encouraged others, including “Snowy” McAllister of Manly and Adrian Curlewis of

Palm Beach. He went on to become a professional lifesaver at

ManlyBeachfor many years.

In

Queensland, two copies of Duke Kahanamoku’s pine board were made for the Greenmount Surf Lifesaving Club. The arrival of the two boards prompted further replicas made and surfed by Sid “Splinter” Chapman, Andy Gibson and a surfer known only as Winders. Prices varied from two shillings and sixpence to seven shillings and sixpence.

In 1919 Louis Whyte, a

Geelongbusinessman, and Ian McGillivray visited Hawai‘i and purchased solid redwood boards from Duke Kahanamoku. The boards were subsequently ridden at

Lorne Point, Victoria.

John Ralston, a

Sydney solicitor and land developer, introduced surfboards at

Palm Beach,

Sydney in 1919.

With such encouragement,

Palm Beachbecame a popular board riding beach, producing several champions and a strong pro-surfboard lobby within the ASLA.

Some of the Surf Life Saving clubs became centers of board riding, clubhouses becoming storage facilities for boards, in addition to being places where club members could gather and hang out.

With the end of World War I in 1918, military technological developments like industrial glues and varnishes were applied to marine craft, including surfboard construction.

In the early years of its establishment, board riding was given little support by the Surf Life Surfing Association. Competitions as part of carnivals were judged subjectively. For example, a headstand scored maximum points although it had little to do with how well one rode the wave. With a growing emphasis on rescue techniques, it was paddling skill that became the focus when it came to surfboard use. Record keeping for surfing events was an after thought. Often, board events were either not held or not recorded, and since the ASLA was in its infancy and basically a New South Wales organization, results were open to dispute.

Amazingly, it was not until 1946 that the first officially-recognized Australian Longboard Championship took place.

However, the first credited Australian surfing magazine was published in 1917. This was Manly Surf Club’s

The Surf, which first published on December 1, 1917. It ran for twenty editions, until April 27, 1918.

In February 1920, Claude West used his board to rescue a swimmer at Manly. The rescuee was the Australian Goveror-General, Sir Ronald Mungo Fergerson, who presented his rescuer with his silver dress watch, in appreciation.

A newspaper report of the “Australian Championships” at Manly, March 1920, records the results of a surfboard race:

1. A. McKenzie (North Bondi)

2. Oswald Downing (Manly)

3. A. Moxan (

North Bondi)

A similar newspaper report of the Bondi Championships, April 1921, records the results of a surfboard race as:

1. A. McKenzie (North Bondi)

2. A. Moxan

Other starters were Oswald Downing and Claude West (Manly).

By 1921, the Surf Life Saving Association printed their first handbook. It probably formed the basis for subsequent publications later entitled the “Handbook of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia.”

At the Australian Championships at Manly in 1922, the board event results were:

1. Claude West (Manly)

2. A. McKenzie (North Bondi)

3. Oswald Downing (Manly)

West, who had apparently dominated the demonstrations, was soon to retire.

Oswald Downing was an early board builder and a trainee architect who had drawn up his own surfboard construction plans. These are possibly the plans printed in the 1923 edition of The Australian Surf Life Saving Handbook.

In celebration of Collaroy SLSC’s victory in the Alarm Reel Race at the Australian Championships at Manly in 1922, swimmer Ron Harris’ family commissioned Buster Quinn (a cabinet maker with Anthony Hordens) to make a surfboard. Quinn made the board from a single piece of Californian Redwood at the Dingbats’ Camp. Before it was completed, however, Harris’ father died and the family left Collaroy. Chic Proctor acquired the board in Harris’ absence and it remains in the clubhouse to this day as the Club’s Life Members Honour Board.

With growing numbers of surf board riders, the Manly Council considered banning surfboards altogether, in 1923, in the interest of the public safety of bodysurfers. This idea was forgotten when one day at the beach, three city councilors witnessed a rescue of three swimmers in high surf by Claude West using his surfboard. Reversing their position, the Council commended the use of surfboards as rescue craft.

At the 1924 the Australian Championships at Manly, the surfboard display was won by Charles Justin “Snowy” McAlister of the Manly Surf Club. As a kid, he had watched Duke ride in 1915. Thereafter, Snowy soon began surfing on his mother’s pine ironing board. “I used to wag school and rush down to the beach with it,” he recalled. “I got away with it a number of times, but she eventually found out because I would come home sunburnt.”

The pine ironing board was followed by a self-made plywood board and his first full size board, a gift from Oswald Downing.

Later, Snowy made his own solid redwood board. “I used to go into the timber yards in the city and buy a ten by three foot piece of wood about two feet thick (sic, inches?), which I had delivered to the cargo wharf beside the Manly ferry.

“I’d lug it home, then carve it, varnish it overnight and try it out the next morning.

“We were getting murdered in those days.

“The boards had no fins.

“We’d go straight down the face of the wave instead of riding the corners as the Duke had done. When we saw him do that we thought he was just riding crooked.”

Starting out on an impressive competitive record, Snowy McAlister won board displays in Sydney in 1923-24 (Manly), 1924-25 (Manly), 1925-26 (North Bondi) and 1926-27 (Manly, second Les Ellinson).

His record at

Newcastlewas even more outstanding, with wins in 1923-24, 1925-26, 1927-28, 1930-31, 1931-32, 1934-35 and 1935-36. All these victories were on solid boards. He competed to 1938 and then made a comeback at the 1956 Olympic Carnival, Torquay.

Snowy was the nation’s unofficial national surfboard champion from 1924 to 1928. He visited

South Africaand

England on the way to the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928, accompanying another Manly Surf Club member Andrew “Boy”

Carlton.

Following the introduction of the

Blake Hollow board to

Australia in 1934, Snowy turned to the surfski as his preferred wave riding craft.

Another noted surfer of this formative period in Australian surfing was Adrian Curlewis. Around 1923, Curlewis bought a used 70 pound board from Claude West, so he could surf regularly at

Palm Beach. This board was replaced by one of similar design in 1926, a board built by Les V. Hind of

North Steyne for five pounds and fifteen shillings, including delivery.

Curlewis became a noted surf performer, becoming somewhat of a star thanks a photograph printed in an Australian magazine in 1936.

Sir Adrian Curlewis was born in 1901. He graduated from

SydneyUniversityand was called to the Bar in 1927. He served in

Malayain

World War II and was a prisoner of war from 1942 to 1945. He held the Presidency of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia from 1933 to 1974, his position as sole Life Governor of that Association from 1974, and his Presidency of the International Council of Surf Life Saving from 1956 to 1973. Curlewis served as a New South Wales District Court Judge from 1948 to 1971, retiring at the age of 70.

Perhaps because of his early board riding experiences and long association with surf lifesaving organizations, he was a noted 1960s opponent of the growth of an independent surf culture centered on wave riding.

At Coolangatta, boardriding continued to expand during the 1920s. Basic competitions (using a standing take-off) were organized and riders included Clarrie Englert, Bill Davies, “Bluey” Gray and later, Jack Ajax. Bluey Gray, in fact, wrote to Hawaiian and Californian surfers in an attempt to learn more about current developments in the sport. Problems in sourcing suitable redwood saw “Splinter” Chapman, one of the coast’s top riders, use local Bolly gum to build boards.

North of Coolangatta, the first full-sized board was probably owned by John Russell of the Main Beach Club, circa 1925.

Circa 1925,

Sydney rider Anslie “Sprint”

Walker surfed at

Portsea, Victoria. When he encountered trouble transporting the board between Portsea and home, he solved the problem by leaving his board at the beach, buried in the sand. The board was eventually donated to the Torquay Surf Live Saving Club, but was later destroyed when the club house burnt down in 1970. Sprint solved this problem, too, by building a replica from Canadian redwood with an adze, the way it had been done originally.

The North Steyne Surf Life Saving Club promoted their 4th annual carnival, scheduled for December 19, 1925 at 2:45 p.m., with a flyer printed by the Manly Daily Press. The noted “Surf and Beach Attractions” included: “1200 Competitors, 18 Leading Surf Life Saving Clubs Participating - Surf Boat Races, Thrills and Spills, Board Exhibitions, All State Surf Swimming Champions Competing.”

The Australian Surf Life Saving Association promoted their annual surf championships, scheduled for February 27, 1926 at 2.30 p.m., with a flyer printed by the Mortons Ltd. Sydney. It emphasized: “Surf Boats, Surf Shooting and Surf Board Displays by Real Champions.”

In the late

1920s, Collaroy SLSC member Bert Chequer manufactured surfboards commercially and 15 shillings cheaper than

North Steyne builder Les Hind.

In the early 1920s, Chequer had been captivated by the likes of board riders such as Weary Lee, Chic Proctor and Ron Harris and made his first surfboard at 17 using a design similar to Buster Quinn’s. As the years progressed, Chequer refined Quinn’s design, producing a board which was held in high regard by many other board riders in the Club. Dick Swift requested he build him a board (the board is still in the Club house) and with delivery of the board a flood of similar requests came his way. So, with this development and little work in his father’s building business to keep him busy, Chequer decided to try his hand at commercial surfboard building – one of the earliest such enterprises in the country. The cost of a Chequer board was £5 which included delivery.

Chequer bought his timber from

Hudson’s timber merchants where it was kiln dried before delivery. While he preferred cedar, its expense meant that he was forced to use Californian Redwood. The board was crafted from a single piece of wood, meaning that Chequer’s small workshop was usually a sea of wood shavings.

A board took just two days to build and was totally shaped by hand. Once shaped, the board was coated with Linseed oil, before two coats of Velspar yacht varnish was applied. In his initial experimentation with the varnish on his own board, the yellow finish it gave off prompted the board to be known as the “Yellow Peril.” Boards were usually intricately marked either with a name, the initials of the owner, or with the Club emblem.

Chequer was soon supplying individuals and clubs up and down the

New South Wales coast and as far away as

PhillipIslandin

Victoria. While the business was relatively successful, there was a downside for Chequer. Because he was a surfboard manufacturer, making money out of what was now regarded as a piece of life saving equipment; the Association claimed he was no longer an amateur by their definition. He was therefore prohibited from surf life saving competition between 1932 and 1936.

In the late 1920s, T.A. Brown and A. Williams used a corkwood board from

Honoluluat Byron Bay NSW.

Eric Mallen purchased a cedar slab that was once the counter of the Commerical Bank, and had it shaped into a fouteen foot board by Jack Wilson. Proving to be too unwieldy, the board was later cut down, decorated and named “Leaping Lena.” On large days, Eric Mallen would leap off the end of the large jetty that ran out from

Main Street to save paddling.

On Sunday, April 26, 1931, a belt and reel rescue attempt at Collaroy in extreme weed and swell conditions resulted in the death of Collaroy SLSC member, George “Jordie” Greenwell. Even though the use of the reel was questionable in thick weed and high swell conditions, the inability of Greenwell to release himself from the belt was the main reason for his demise. Despite demands on the SLSA’s Gear Committee, the “Ross safety belt” – designed to ensure the lifesaver from just such an entanglement – did not become compulsory for member clubs until the 1950s. Greenwell was posthumously awarded the Meritious Award in Silver, the SLSA’s highest honor.

While Greenwell’s drowning resurrected the debate on surf belts, there were two more immediate and positive developments from the drowning. The first was an intensification of Association trials using waxed line to see if it would “overcome the difficulty of seaweed.” The other was the Association’s endorsement of the use of surfboards as life saving equipment. In the Greenwell drowning itself, the surfboard had proved its usefulness in surf with a high seaweed content.

In the 1920s, surfboards had been used by a number of clubs as rescue apparatus. While the line and reel remained the predominant rescue technique, the surfboard rivaled the surf boat for the number of rescues accorded to it each season. Such use, however, had been against the wishes of the Association and lifesavers like Manly’s Claude West were reprimanded for their use.

During the 1929-30 season, the Collaroy Annual Report recorded rescues performed using surfboards, noting two such. The following season, four surfboard rescues were recorded. The figure was probably much greater, in reality, due to the fact that surfboards were often used to assist tired swimmers before they got into actual difficulties. While confined almost exclusively to surf club use, surfboards were usually only used by members who were not on patrol duty.

The data in club annual reports demonstrated to the Association that most clubs saw surfboards as useful rescue craft. Within the Association, individuals such as Greg Dellit, Adrian Curlewis and Bert Chequer (who had joined the Board of Examiners) began to champion the surfboard. Eventually, interested parties agreed that surfboards should be trialed so their usefulness could be gauged. These trials were held in the swimming pool of the Tattersals Club in

Sydney. The trials confirmed the usefulness of surfboards as flotation devices in multiple and lone lifesaver rescues. The fact they mostly went over rather than through sea weed was also noted.

Long Beach, USA, 1910-1927

By the start of the 1930s,

Southern California’s surfing epicenter was located at Corona del Mar. But SoCal surfing had begun up the coast first at

Venicein 1907, then Redondo and

Huntington, spreading out from those beaches.

Surfing’s evolution in the Los Angelesarea can be seen in a reading of the local newspapers of the period, especially the ones around Long Beach. Surfing in Long Beach? It is hard to imagine today, but once upon a time – before the breakwater was built in the early 1940s and before the area’s massive landfill was undertaken – not only did excellent surf break upon its shores, but Long Beach was once considered “the Waikiki of the PacificCoast.” Today, despite the disappearance of the long beach that gave the city its name, some surfers still remember the old days and for those of us a bit younger, we have the newspaper record:

Long Beach Press, April 7, 1910 – “SUGGESTS USE OF SURF BOATS: VISITOR JUST IN FROM HAWAII FAVORS NEW AMUSEMENT FOR LONG BEACH

“W.P. Wheeler of Monroe, Mich., who has arrived in Long Beachto spend the summer after a winter in Hawaii, suggests that some enterprising man with a little money build and put in operation a lot of surf boats, for which Waikiki beach, Honolulu is famous.

“Mr. Wheeler says that Long Beachis the only beach he has ever seen which can compare with the famous Waikiki, and that the surf rolls here exactly as it does at that beach.

“‘When I saw those catamarans, or surf boats, operated at

Waikiki,’ said Mr. Wheeler, ‘I wondered why the Pacific coast beach resorts did not take to them. I was told while in

Honolulu, by an admirer of Waikiki, that no beach on the

Californiacoast was as shallow and long as

Waikiki. Now I know that the fellow was not well informed, for the beach here is exactly like the Hawaiian beach.’”

To my knowledge, the first recorded lifesaving action using surfboards in U.S. Mainland waters took place on September 3, 1911:

Daily Telegram, September 4, 1911 – “TWO LIVES SAVED BY SKILLFUL USE OF HAWAIIAN SURFERS

“One of the most novel rescues every pulled off in the surf at Long Beach was accomplished yesterday afternoon on the beach west of Magnolia Avenue when Paul Rowan of Long Beach and a stranger who slipped away before his identity could be discovered, were saved from drowning by Charles Allbright and A.J. Stout.

“The two rescuers were also nearly exhausted and were helped to the beach during the latter part of their spectacular trip by the hotel life guard, John Leonard, who was unaware of the trouble until he saw the men struggling to reach shore against a strong rip tide.

“Both the rescuers met and became close friends in Honolulu and brought Hawaiian surfboards over with them recently to try them out in the local surf. Paul Rowan, who is a strong swimmer, was out beyond the end of the lifelines, which extend from the beach to a point beyond the breakers. He was swimming about, enjoying the exercise when he heard a cry from a man who was nearer the shore, but just beyond the breakers.

“‘For God’s sake, help me. I have a wife on shore,’ gurgled the stranger, a man of about thirty years of age, as he began to sink.

“Rowan went to his help with a swift overhand stroke and caught him just as he was sinking a second time in the strong offshore current.

“The stranger immediately grabbed hold of Rowan and held him so that he had to fight to free his arms. Rowan was also dragged under. It was at this point that Allbright and Stout, on their surfboards, became aware of the situation.

“Allbright grabbed Rowan, who was dizzy from his forced immersion and placed him on his surfboard. Stout did the same for the stranger. Just then a succession of big breakers came along and the two men, with their burdens, coasted magnificently inshore against the rip tide.

“The peculiarity of the Hawaiian surfboards was to a large extent responsible for the effectiveness of the rescue of both the stranger and his first rescuer, Paul Rowan. The boards are made of the beautifully grained koa wood of the Hawaiian Isles and are six feet long. They are three inches thick and eighteen inches wide.

“Both Allbright and Stout are expert surfboard riders and for years coasted on the foaming breakers which run in on the beach between Diamond Head and Honolulu. There the mountain high breakers travel at great speeds for a distance of nearly half a mile. Yesterday they were riding the breakers with the greatest ease in front of the VirginiaHoteland a large crowd was watching them as they stood up on the boards and coasted rapidly ashore. The rescues yesterday were probably the first of the kind. The success of the men with their boards may result in the general use of the same type at the beach.

“Both Allbright and Stout made light of the incident, and from information supplied from other sources it was learned that they frequently make similar rescues out in the

Hawaiian Islands.”

Long Beach Press, February 26, 1921 – “NOVEL SURF BOARD AND CANOES MADE

“Surf-boating has made such an appeal to visitors to Long Beach during the past year that Victor K. Hart, manager of Venetian Square; and T. Bennett Shutt, local building contractor, have completed arrangements to manufacture surf boards and surf canoes here in quantity. A temporary factory has been opened and twenty of the surfboards and a dozen canoes are now being built.

“Erection of the flood control jetties has checked the ocean currents to such an extent that splendid surf-boating is now to be enjoyed on the west beach. The surfboards under construction here were designed by Hart and Shutt and are said to be lighter and different in shape to the Hawaiian island boards.”

One of Long Beach’s first surfers was Haig (Hal) Prieste, who won an Olympic diving medal at the 1920 Olympics. There, he met Duke Kahanamoku and accepted an invitation to visit him in Hawai‘i, where he took up surfing and became an honorary member of the Hui Nalu:

Long Beach Press, May 3, 1921 – “LOCAL BOY TO ENTER BIG MEET IN HAWAII

“Haig Prieste, Long Beach boy and former Poly High student, winner of third place in the Olympic games diving contests, leaves Friday for San Francisco en route to the Hawaiian islands, where he will enter the junior national high diving contest which is to be a feature of a big aquatic carnival to be held in Honolulu. Prieste will be the only swimmer to enter the meet from the mainland, a special request for his presence having been made by the swimming officials at Honolulu.

“Following his appearance at

Honolulu, Prieste may continue to the

Antipodes where he has been requested to enter a number of contests with the best of the Australian swimmers and divers. Whether he will make this trip or not depends upon contracts which he has with motion picture concerns. Prieste formerly was connected with Mack Sennet and with the Rollin and Gasnier studios doing ‘dare devil’ stunts in comedy productions. He has achieved quite a reputation locally as a sleight of hand entertainer in addition to his prowess as a high diver.”

Daily Telegram, August 15, 1921 – “HAIG PRIESTE HOME FROM THREE MONTHS OF HAWAIIAN TOUR: HAS MAMMOTH SURFBOARD GIVEN HIM

“Haig Prieste, Olympic diving champion, returned to Long Beach with a ukulele, an oversize surfboard and an interesting story of three months in the Hawaiian Islands. He intended to remain three weeks when he left as the only American entrant in the Hawaiian carnival staged in the latter part of May. The charm of the islands, the determination to master Hawaiian surf board riding – and the ukulele – and an opportunity to gather a couple of spare diving championships kept him several weeks overtime.

“He won the junior national high diving title and the springboard diving championship of a half dozen islands. He brought with him the Castle and Cook trophy and several others of lesser significance. He was the guest of honor and an honorary member of the Hui Nalu swimming club, the leading aquatic organization of the islands.

“Prieste and Duke Kahanamoku palled around together at Hilo for a time. Prieste astonished the natives when he learned to ride the gigantic surfboards standing on his hands. ‘It’s the greatest sport in the world,’ he said today.

“Prieste says that the expert Hawaiian surfriders are able to ride for three-quarters of a mile on their boards. They have grown up with a surfboard in one hand, and by learning the formation of the coral reefs and the various currents, they are able to pilot their boards for great distances in a zigzag course. The waves bowl them along at a speed of 35 miles per hour. There is a great knack in catching the wave at the proper angle, Prieste says. Unless the board is pointed diagonally at the correct angle at the correct moment both board and rider will be dumped on the coral floor of the ocean. Prieste spent from 8 to 10 hours in the water each day.”

Press-Telegram, December 31, 1926 – “BEACH GREATEST

“Board surfing has been growing in popularity year by year. While most of the boards used are short and only for the surf after it has broken, yet there have developed some who have learned to ride the waves while they are still huge and green without any white water. Some of the beach guards have mastered an art before confined to the surfing beaches of the Hawaiian Islands.

“Even some of the

Long Beach girls have become proficient in this exciting water sport.”

Early Californiatandem surfing:

Press-Telegram, March 18, 1927 – “TWO DARE DEATH

“A special exhibition of fancy riding on surfboards will be performed by Elmer Peck and Miriam Tizzard at AlamitosBay. Peck has attained national stunts that he has performed in all parts of this country as well as in the waters off Hawaiiand the South American republics.

“Miss Tizzard is a local girl and though she has only been under Mr. Peck’s direction for two weeks he regards her as one of the most apt pupils that he has ever trained. He says that she is perfectly at home on the elusive surfboard. Special stunts in which the two combine will be a feature of the program offered.”

Coronadel Mar, 1923-1927

Although there were small numbers of “Roaring ‘20s” surfers riding waves at a limited number of breaks from Santa Monica to San Diego, the most popular break was Corona del Mar. This had probably as much to do with the nightlife at Balboa, north across the channel leading to NewportHarbor, as it was to Corona’s exceptionally nice set-up, surf-wise. The good surf at Corona was all about the south jetty.

Although not originally intended for surfers, the cement jetty at Corona del Mar was a boon for surfriders. The 800-foot long jetty stretched from the rocks at Big Corona all the way to the beach. When the swells were running, a surfer could launch from the end of the jetty, ride in next to it for approximately 800 feet, then climb up a chain ladder, run out on the jetty and do the same thing all over again. Perhaps more importantly, waves jacked up at Coronaunlike they did anywhere else – also due to the jetty.

In 1923, two beacon lights were installed at the jetty entrance. These were written about in a Long Beach Press article, in December: “The two beacon lights at the end of the jetty protecting the entrance of Newportharbor are complete and have been turned over to the care of Antar Deraga, head of the Balboa life saving guards… The lights are about thirty feet above the ocean level and can be seen by all ships passing on the east side of Catalina.

“The outer beacon light is equipped with a three-fourths foot burner and will burn about 160 days. It flashes one second and five seconds dark. It is equipped with a sun valve for economy of operation. The inner beacon light is equipped with a five-sixteenths-foot burner without sun valve. It should burn 200 days. This beacon flashes every two and a half seconds.

“The government lighthouse service will also supply the keeper here with a lifeboat for use in rescue work. It will be in charge of Mr. Deraga, who is known as one of the most efficient lifeguards on the coast. Before coming here he made an enviable record in Europe and has recently been made a member of the Royal life saving guards of

Englandand given a service medal in recognition of heroic service in the

English Channel and also for saving the life of an English lady in this harbor last summer.”

Antar Deraga was also one of those who, along with standout surfer and Olympic champion Duke Kahanamoku, helped rescue the majority of the crew of the Thelma when it floundered off Newport Beach in 1925:

“Battling with his surfboard through the heavy seas in which no small boat could live, Kahanamoku, was the first to reach the drowning men. He made three successive trips to the beach and carried four victims the first trip, three the second and one the third. Sheffield, Plummer and Derega were credited with saving four; while other members of the rescue party waded into the surf and carried the drowning men to safety…

“The accident occurred at the identical spot near the bell buoy where, almost to a day a year ago, a similar accident occurred and nine men were drowned. Two of the bodies were carried out to sea by the undertow and were never recovered.

“Captain Porter expressed the belief yesterday that at least eight or ten more would have been drowned had not Kahanamoku and Derega been ready with immediate assistance…

“The Hawaiian swimmer was camped on the beach with a party of film players and was just going out for his morning swim when the boat was wrecked. The lifeguards were just going on duty.”

There was an established record of difficulty for boats leaving and entering the Newport Channel on a good swell. In 1927, the city of

Newport voted $500,000 for a harbor expansion that included changes to the jetties. In 1928, the city approved $200,000 for work on both the west and east jetties. It was this later work that would forever change surfing at Corona del Mar – especially the surf adjacent to the east jetty – and be lamented by surfers who considered

Corona the main surfing

beach of Southern California.

Surfing’s first dedicated surf photographer

Doc Ball eulogized the early surf scene at Corona del Mar, when he later wrote in 1946: “We who knew it will never forget buzzing the end of that slippery, slimy jetty, just barely missing the crushing impact as the sea mashed into the concrete. Nor will we forget the squeeze act when 18 to 20 guys all tried to take off on the same fringing hook. And do you remember the days when you waited near that clanging bell buoy for the next set to arrive?

CoronaDelMar’s zero surf was hell on the yachtsmen but – holy cow – what stuff for the Kamaainas. Yes! Those were the days.”

During the area’s boom-days of the 1920s, a housing development originally named Balboa Bay Palisades was created in 1923 and morphed into what we now call Corona del Mar. During that decade, the area’s income came mostly from the Rendezvous dance hall, gambling and bootleg liquor. The Rendezvous Ballroom was the place to be and a major destination for touring big bands of the time. On a Saturday night the town bore a resemblance to

Bourbon Street, in

New Orleans, during Mardi Gras. A number of businesses were involved in gambling. More on the Rendezvous when we get to talking about

Gene “Tarzan” Smith.

The FirstPacificCoast Surfriding Championship, 1928

While Corona del Mar was in its glory days as the center of Southern California surfing, history was made there with the creation of the Pacific Coast Surfriding Championships. Word of it began on July 16, 1928 when a Long BeachPress-Telegram announced: “SURFBOARD CLUB WILL HOLD TITLE MEET AT HARBOR.” The article read: “The Corona Del Mar Surfboard Club, which claims to be the largest organization of its kind in the world, will hold a championship surfboard riding tournament at the CoronaDel Mar beach at the entrance to NewportHarbor on Sunday, August 5.

“Some of the most notable surfboard riders in the world are expected to compete, including the famous swimmer and surfboard rider, Duke Kahanamoku, Hawaiian champion;

Tom Blake of Redondo, who won two championships, and Harold Jarvis, long distance swimmer of the Los Angeles Athletic Club. Some of the surfboard riders are predicting that new world records will be made here during the meet. So far fifteen surfboard artists have signed up, including some from as far away as

San Francisco. It is planned to make it an annual event.”

On the day of the contest, August 5, 1928,

the

Press-Telegram reported: “PLANS COMPLETED FOR SURFBOARD RIDING TILT.” It went on: “Preparations have been completed for the Pacific Coast surfboard riding championship tournament, to be held at Corona Del Mar, the entrance to Newport Harbor today. Part of the entrance to the harbor is said to be only surpassed by some Hawaiian beaches for surfboard riding.

“Duke Kahanamoku and other well-known surfboard artists will compete. Besides surfboard riding the program will include canoe tilting contests, paddling races and a life-saving exhibition by surfboard riders. In addition to Kahanamoku, other well-known members of the club include Tom Blake of Redondo, Gerard Vultee and Art Vultee of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, Clyde Swedson of the Hollywood Athletic Club, and others.”

More important than the results of who won what, the big story of this first-ever surf contest on the U.S. Mainland was the first-ever unveiling of the hollow surfboard in competition. Tom Blake brought his drilled-hole hollow board innovation and a regular 9-foot 6-inch redwood surfboard back with him by boat from Hawai‘i. Armed with his partially hollow

oloreplica, Tom subsequently won the first Pacific Coast Surfriding Championships – which he had also helped organize.

Held under direction of Captain Scheffield of the Corona del Mar Surfboard Club, the championship’s main event was a paddle race from shore to the bell buoy, followed by a surf ride in. “500 yards and back; 1

st back to win,” Tom remembered.

In later documenting the event for his protégé

Tommy Zahn in 1972, Tom wrote: “Situation: about 8 or 10 men, including Gerard Vultee (late co-founder of Lockheed; an aeronautical engineer; designer of aircraft and surfboards). He had the longest board; 11-feet. I had a 9’6’ broad riding board. I figured he would be 1

stout at the break and therefore should get the first wave in.

“I had this (1st one only) 15-foot paddle board with me for the paddling race (115 lb.). So I decided to use both boards in the surfing race. Had them both on the beach as the starting gun went off. Everybody got a good head start; Vultee in the lead. I slowly proceeded to put the 15’ P.B. in the water, then went back to get the 9 ½ job; placed it upon the P.B. and started after the field, now 50 yards out. Slowly caught and passed them at 300 yards and arrived at the starting break [the bell buoy] alone with a minute to spare – discarded the long board and lined up for the 1st wave. They were about 6 or 7 feet high; not large, but strong.

“Vultee arrived first, then the rest; we all had to wait a few minutes for a set of waves. Vultee and me took after the first one. He got it and took off on the

left side, for shore. But, the second wave was a bit bigger. I got it and slid right. Vultee’s wave petered out in the channel; mine carried me all the way in, opposite the jetty and to shore for a win. There was a movie outfit there; a newsreel deal. I later saw the ride and had a close-up [made]; someone probably still has it.”

Tom used two boards that historic day – a first, in itself. He used the drilled-hole hollow board for paddling out and a more conventional board for riding waves in. Having a board strictly for paddling was unheard of up to this point. Up to this point, everyone had competed in paddling races on surfboards. Some

Californiaold-timers recalled of that day that it was the first time they had ever seen a surfboard turned. Dragging either the left or the right leg in the water accomplished this. His surfboard was 9-feet, 6-inches long, but the paddleboard was 16 feet and weighed 120 pounds.

Blake wrote of his huge drilled-hole

olo design paddleboard: “When I appeared with it for the first time before 10,000 people gathered for a holiday and to watch the races, it was regarded as silly. Handling this heavy board alone, I got off to a poor start, the rest of the field gaining a thirty-yard lead in the meantime. It really looked bad for the board and my reputation and hundreds openly laughed. But a few minutes later it turned to applause because the big board led the way to the finish of the 880-yard course by fully 100 yards.”

“Later,” after the main event, “they held a 440 yard board race, paddling. I let Vultee lead for most of it, then breezed by him on the new semi-hollow paddle board. Received a statue of a swimmer and a cup. Still have the statuette of a swimmer; the cup is held by some club; don’t know who. It has Pete’s [Peterson] name on it for many later winnings.”

Next day, the Long BeachPress-Telegram announced: “LOS ANGELES MAN, TOM BLAKE, WINNER OF EVENTS OF SURFBOARD CLUB.” The article continued: “The aquatic powers of Tom Blake, bewhiskered athlete of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, enabled him to win over an assemblage of swimmers in the meet held yesterday afternoon in front of the Starr Bath House on the CoronaDelMar beach. Blake took two of the first places, winning easily the surfboard contest and the paddling race. He was awarded silver trophies for his championship.

“Several hundred people lined the beach to witness the contest held under the auspices of the Corona Del Mar Surfboard Association. The fact that Duke Kahanamoku, famous surfboard rider, could not be present did not detract from the excitement of the day.

“The Corona Del Mar Surfboard Club has been sponsored by Captain D.W. Sheffield, manager of the Starr Bathhouse. It is said to be the only organization of its kind on the PacificCoast.

“The results of the contest were as follows: Quarter-mile surfboard race, won by Tom Blake, L.A.A.C.; second, Gerard Vultee,

CoronaDel Mar; third Dennie Williams,

CoronaDel Mar. Paddling race was won by Tom Blake; second, Dennie Williams.”

The first first-place PCSC trophy “was first won by Tom Blake in 1928 at

CoronaDelMar,” confirmed Doc Ball in his classic collection of early

Californiasurfer photos,

CaliforniaSurfriders, 1946.

Because the original trophy was not much to speak of, Blake had a nicely embossed trophy cup made in order to pass on to succeeding winners.

He donated this trophy “to be the perpetual cup for the above mentioned event. Winners since 1928 are inscribed on the back of it.” A good photograph of it appears in Doc’s book. He added that “World War II precluded any possibilities of a contest from 1941 through 1946.”

The Pacific Coast Surfriding Championships became an annual event, dominated for 4-out-of-9 years by

Preston “Pete” Peterson, who reigned as

California’s recognized top surfer throughout the 1930s. Other early winners of the trophy included Keller Watson (1929), Gardner Lippincott (1934),

Lorrin “Whitey”Harrison (1939) and Cliff Tucker (1940).

As for

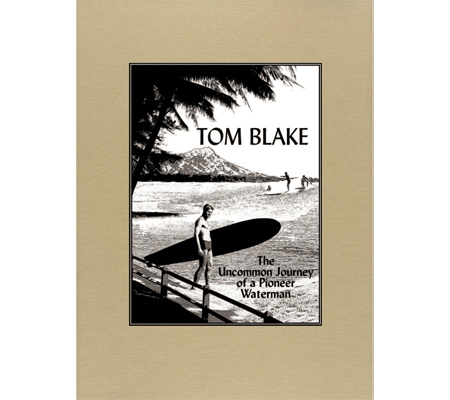

Tom Blake, although he met with competitive success on the U.S. Mainland, his eyes were mostly on the

Islands. “My dream was to introduce, or revive, this type of board in

Hawaii where surfboard racing and riding is at its best,” he wrote in his 1935 edition of

Hawaiian Surfboard, the first book ever published solely about surfing. “This seems to have materialized...”

Blake – originally a competitive swimmer – rose to prominence in the emerging world of surfing, following his restoration of traditional Hawaiian surfboards and his creative innovation of those designs into what became known as “the hollow board” – both surfboards and paddleboards.

After restoring Chief Paki’s boards for the

BernicePauahi BishopMuseum, Blake built some replicas for himself. In an article entitled, “Surf-riding – The Royal and Ancient Sport,” published in a 1930 edition of

The Pan Pacific, he wrote: “I... wondered about these boards in the museum, wondered so much that in 1926 I built a duplicate of them as an experiment, my object being to find not a better board, but to find a faster board to use in the annual and popular surfboard paddling races held in Southern California each summer.”

During the

1920s, surfboards weighed between 75 and 150 pounds. Because of the length of the board and the wood it was made of, Paki’s

olowas considerably heavier than the heaviest

Waikikiboard of the day, all of which were of solid wood construction. On a whim, Blake took his 16 foot

olo replica board and, in his own words, “drilled it full of holes to lighten and dry it out, then plugged them up. Result: accidental invention of the first hollow surf-board.”

Blake’s “holey” board ended up exactly 15 feet long, 19 inches wide and 4 inches thick. Because it was partially hollow, this board weighed only 120 pounds.

This was the “hollow” board he used in the first Pacific Coast Surfing Championships at Corona del Mar.

Following his win of the first Pacific Coast Surfing Championship at Corona del Mar in 1928, Blake took his hollow board back to Hawai‘i with him and took on the famous races held at the AlaWaiCanalannually. By this time, he had given up on filled-in drilled holes in favor of a hollowed-out chamber approach.

“I introduced at

Waikiki a new type of surfboard,” Blake wrote of his hollow board. It was, “new so the papers said, and so the beach boys said, but in reality the design was taken from the ancient Hawaiian type of board,” his 1926 replicas of them, and “also from the English racing shell. It was called a ‘cigar board,’ because a newspaper reporter thought it was shaped like a giant cigar.”

Of Blake’s hollow

olo-inspired design, Dr. D’Eliscu of the

HonoluluStar-Bulletin wrote that “The old Hawaiian surfboard has again made its appearance at

Waikikibeach modeled after the

boards used in the old days. A practice trial was held yesterday at the War Memorial Pool, and to the surprise of the officials, the board took several seconds off the Hawaiian record for one hundred yards.”

Blake referred to this modern

olo design as the racing model; in essence a true paddleboard. He built his surf riding model surfboard, “Okohola,” a month later, in December 1929.

The hollow paddleboards and surfboards Blake now made, “differed from the olo in that they were flat-decked, built of redwood, and hollow,” wrote Finney and

Houstonin

Surfing, The Sport of Hawaiian Kings, many years later. “They were excellent for paddling and also successful in the surf. Like the olo they were well adapted to the glossy rollers at

Waikiki. A man could catch a wave far out beyond the break, while the swell was still a gentle, shore-rolling slope, and the board would slide easily along the wave, whether it grew steep and broke, or barely rose and flattened out again.”

Duke Kahanamoku told his biographer that Blake’s first experiments had actually been initially “predicated on the belief that faster rides would be generated by heavier boards. But the turning problem became bigger with the size of the board; a prone surfer was compelled to drag one foot in the water on the inside of the turn, and this only contributed to loss of forward speed. If standing, he had to drag an arm over the side, and with the same result of diminishing momentum.

“Paddleboards are still with us today, and they are obviously here to stay,” Duke affirmed. “Some fantastic records have been established with them. And the sport of paddleboarding has naturally drawn some outstanding men to its ranks. It is a long list, a gallant list.”

Recapping its initial evolution, Blake said his first hollow board “was purely for racing, and I soon followed it with a riding board sixteen feet long. The new riding board model was a great success [‘Okohola’].” Blake added with some pride that “Duke Kahanamoku built his great 16-foot hollow redwood board along about the same time…”

Tom Blake set his first world’s record in paddling at Ala Wai in December 1929. It came after years of discipline and development of skill in racing under stress. He had swum in hundreds of races during the eight years previously and won the first official Californiasurfing contest (the PCSC) just the year before. The Honolulu Star-Bulletinfrom December 2, 1929, reported the event the day after: “BLAKE SETS 100-YARD SURFBOARD PADDLE MARK. Big Crowd On Hand To Take In Sunday Races; Outrigger Club Clean Sweeps In AlaWai Program of 18 Popular Events.” The Honolulu Star-Bulletin went on:

“Demonstrating the possibilities of such a surfboard, Tom Blake of ‘cigar surfboard’ fame, yesterday paddled his pet water rider to a new 100-yard Hawaiian record (world’s record) at the Ala Wai where he negotiated the distance in 35 1-5 seconds, bettering the old mark by five full seconds in an exhibition witnessed by a crowd of 1000.

“The former record was 40 1-5 seconds made last year by Edric Cooke. More plumes are added to his [Blake’s] achievement when it is considered that he had to paddle through the water against a stiff wind and a tide.

“The ‘cigar surfboard’ just glided through the water without a splash and it was an uncanny sight. Blake was in excellent shape and worked his arms tirelessly to set the new world record.”

“The exhibition,” continued the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, “was the feature to a program of surfboard races staged by the recreation commission of the city. The events were put on to prepare those interested in surfboard paddling for the big races to be held during the Christmas holidays.

“The number of automobiles and the large crowds that gathered on both sides of the canal surprised the officials who helped revive the interest in an activity which typifies the islands…

“Sixteen paddle events were conducted in two hours and the timers, judges, clerks and other officials were kept running up and down the banks following the start then taking the finish…

“The Outrigger Canoe club, under the guidance of George (‘Dad’) Center, romped away with all the honors, as the other organizations did not believe that a contest of this kind would be successfully held.

“The appearance of the smoothness of the cigar-shaped board, and the quiet, reserved and impressive showing of its maker and paddler,

TomBlake, attracted more than usual interest. Everybody wanted to use that type of board and the success and speed of this board showed itself in the number of races that were won by the individuals using it.

“Never before in any open races have so many boards been collected in one place. It required a private truck to haul all the surfboards from the Outrigger and Hui Nalu clubs to

AlaWai...”

Perhaps as significant as the wins that day, were resentments by some surfers and paddlers toward the hollow board and its creator. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin noted the resistance to this new type of watercraft: “The question was raised by the officials as to a standard board to be required in all future open competition. The feeling was against this proposal. The officials felt that no board designed to ride the surf could be barred from any of the races scheduled.

“The result of Sunday’s special events assures a number of new records on Christmas Day, when a special program will be held for surfboard followers…”

“This board was really graceful and beautiful to look at,” Tom wrote proudly of his carved chambered paddleboard, “and in performance was so good that officials of the Annual Surfboard Paddling Championship immediately had a set of nine of them built for use...”

Not everyone enthusiastically embraced hollow paddleboards and hollow surfboards. Later, when hollow boards became the standard at many beaches, solid boards were still preferred by some surfers. Doc Ball’s California Surfriders, featuring photographs taken primarily during the 1930s, shows a large number of solid boards in use.

Blake’s world record-breaking wins in both the 100-yard and half mile paddling events of the Hawaiian Surfboard Paddling Championships actually put him into disfavor with some Hawaiians. Resistance to his new designs hit a high point in the December 1, 1929 race. There was an initial attempt to disqualify him, some saying that he was not using a surfboard. Well, they were right on that account. Up until the Pacific Coast Surfing Championship the year before, there had been no such thing as a “paddleboard” specifically used for paddle racing.

Popular local Tommy Keakona, himself a champion of the 1928 Ala Wai races, refused to compete against Tom in protest over his use of the hollow paddleboard.

Other “purist” Hawaiian surfers and distance paddlers demanded that only conventionally shaped and solid paddleboards be allowed to race. Other paddlers lobbied for the new design, claiming, rightfully, that it “marked the beginning of a new era in surfing and paddling.”

The hollow board’s detractors were not sufficient in number to keep Blake from competing, that day, nor the other paddlers using hollow boards. Referring to Blake’s board as “The Cigar Water Conqueror,” a Honolulu Star-Bulletin article written by Francois D’Eliscu documented Tom’s win with this headline: “3000 WATCH SURFERS RACE UPON ALA WAI CANAL. Every Record in History of Sport is Shattered; Cigar Board Comes Into Its Own.” D’Eliscu went on to write: “More than 3000 spectators crowded the banks of the Ala Wai this morning to witness the championship surfboard races in which every record in the history of the sport was shattered.

“Never before was such a contest so keenly fought. Remarkable times were made in the 10-event program.

“The cigar-shaped board was supreme. Each paddler showed speed, smoothness and wonderful control in handling the thin, light, fast-moving planks.

“Tom Blake, originator of the cigar shaped board, staged a surprise unknown to even his coaches when he appeared with a hollow carved cigar board. In the first event on the program, the half-mile men’s open, Blake won in 4 minutes 49 seconds, beating the old record by 2 minutes 13 seconds.

“T. Keakona, last year’s title holder, refused to enter the races, due to the type of board used by Blake.

“The feature event of the morning was the 100-yard open championship. Eight men from three of the best surfboard organizations started. Tom Blake, O.C.C.; Sam Kahanamoku, Hui Nalu; and Fred Vasco of the Queen’s Surfers, finished in the order named.

“The race was exciting from the gun. Tom with his powerful, easy, mechanical stroke and perfect balance found Sam a real competitor. The finish found Blake just a few inches ahead of the versatile swimmer. The time of 31 3-5 seconds for this race was better than last year’s 36 1-5 seconds.”

Another Honolulunewspaper article, written by Andrew Mitsukado, also documented Blake’s wins: “EIGHT RECORDS LOWERED IN MEET. Cigar-shaped Board Is Big Hit, Tom Blake Is Big Star.” Mitsukado continued: “Eight old records went whirling into oblivion and two new marks were established at the sixth annual Hawaiian championship surf board paddling races, sponsored by the Dawkins, Benny Co., yester morn in the Ala Wai before a monstrous crowd which was kept on the well-known edge throughout the ten event program.

“The newly devised cigar-shaped surfboards assisted tremendously in creating the new marks.

“Tom Blake of the Outrigger Canoe Club proved to be the big star of the meet, winning two individual events – the 100 yards men’s open and the half-mile open – and paddling anchor on the triumphant Outrigger team in the three-quarter mile club relay. He used a cigar-shaped board of his own invention and came through with flying colors.

“All of the races were hard fought and competition was keen, furnishing thrills after thrills for the spectators…”

“The half-mile record of seven minutes and two seconds was cut that year,” Tom wrote of the 1929 Annual Surfboard Paddling Championship, “to four minutes and forty-nine seconds and the hundred-yard dash was reduced from thirty-six and two-fifths seconds to thirty-one and three-fifths seconds. This made me the 1930 champion in the senior events and, incidentally, the new record holder. But as is true in yacht and other similar racing, I won because I had a superior board. This was the first cured or hollowed out [paddle] board to appear at

Waikiki. As the racing rules allowed unrestricted size and design, I staked my chances on this hollow racer whose points were proven for now all racing boards are hollow.”

But Blake’s win “was a ‘hollow’ victory,” underscored Tom’s friend Sam Reid, who also competed in the Championship. Playing on words in a surfing memoir published in a 1955 edition of the

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Reid added that “Blake had hollowed out his 16-foot cigar board to a 60 pound weight, compared with an average 100 to 125 pounds weight of the other 9 boards in the 100.”

“Oh, yeah!”

Santa Monica lifeguard Wally Burton told a little bit about what was behind the resentment, adding his own take on it. “He was very innovative. Yeah, he had a good, active mind and… when he was over in the

Islandsthere, he was winning everything. You know, the Duke was the all-time great over there, at that time. And he [Tom] went over there and he took everything away from the Duke. As a matter of fact, they didn’t like Tom too well over in the

Islands [after his competitive wins], because Duke was the hero.”

“Reverberations of the ‘hollow board’ tiff were heard from one end of the Ala Wai to the other,” recalled Sam Reid around 1955, “and echoes can still be heard at Waikiki even today – 25 years later. At a meeting of the three (surfing) clubs, Outrigger, Hui Nalu and Queens, held immediately after the disputed races… it was decided that… there would be no limit whatever on (the design) of paddleboards.”

It is a sad fact that much resentment over his lightweight designs remained after Tom’s Ala Wai wins. Because of the 1929/1930 Ala Wai controversies, Tom only entered the race one more time, the following year.

Impressively, Tom’s half-mile record of 4:49:00 stood until 1955. It was broken by

George Downing, who covered the course in 4:36:00 on a 20-foot hollow balsa board. Blake’s board had been a 16-foot hollow redwood.

Other long-standing records held by

Tom include the world’s record for the 1/2 mile open and 100 yard dash in paddleboard racing. They were held for twenty-five years.

When Tom competed in the Ala Wai contest in early 1931, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin published word of his participation, some of the history of the race and a little about surfing’s history in Hawai’i: “Announce List of Officials to Handle 1931 Surfboard Races,” headlined the article written by Francois D’Eliscu. “Any Type of Board Can Be Used This Year; Races Will Be Held at the AlaWai on January 4; New Kind of Board Will Be Introduced.

“The seventh annual surfboard paddling Hawaiian championships to be held Sunday morning, January 4, 1931, on the Ala Wai canal, promises to be the most interesting event ever held for the paddlers of Oahu… All of the titleholders of last year are entered and the ruling permitting any kind of board in the various races means new records...

“Tom Blake, who startled the community with his cigar-shaped hollow board and smashed all existing records, is reported to have another new type board that is faster and lighter than the one he won with so easily last year.”

Under the subheading of “‘Sport of Kings,’” D’Eliscu continued: “Surfboard racing in Hawaii is known as the ‘sport of kings’ on account of its association with the history and tradition of old-time Hawaiiwhen the chiefs competed on large heavy boards.

“Many of these relics are on exhibition in the museum and it is here where Tom Blake spent many an hour studying the shape, weights and speed of the boards, which prompted him to build his cigar-shaped board…

“Committees and officials have been selected to conduct the meet. The group in charge of the events are: Honorary chairman, ‘Dad’ Center; sponsors, C.G. Benny and H.L. Reppeto; Gay Harris of the Outrigger Canoe Club; Charles Amalu from Queen Surfers, and David Kahanamoku, representing the Hui Nalu swimming club.

“The officials in charge of the meet are as follows: Referee Duke P. Kahanamoku; clerk of course, David Kahanamoku; starter, G.D. Crozier; timers, DadCenter, A.H. Myhre, R.N. Benny, C.A.Slaght, R.J. Thomas and William Hollinger.

“Judges, Dr. Francois D’Eliscu, T.C. Gibson, Henry Sheldon and V. Ligda; recorder, H.L. Reppeto, and Gay Harris will be in charge of the equipment…

“Cecil Benny, who has been responsible for the continuation of the surfboard races and competitions, deserves a great deal of public commendation for his interest in keeping the Hawaiian sport alive.”

Blake’s superior designs were not the only factor in his success. He was also a tremendous swimmer, paddler and overall competitor. Two decades later, his protégé Tommy Zahn paddled the Ala Wai, for practice, with Hot Curl surfer Wally Froiseth’s protégé George Downing. At first he thought his watch was off because he could not achieve Blake’s times on an evolved paddleboard with superior training.

During this period, Tom was coming out with a new board every year. He was driven to refine his designs, and by the end of the 1930s, both his surfboards and paddleboards were very different from what he had started out with a decade before. As far as the controversies at Ala Wai were concerned, Tom learned that good intentions do not always breed good feelings. Because of his competitive wins, he later said that he became a version of “The Ugly American.” Specifically, Tom recalled, “I discovered too late that beating the locals at their own game, in front of their families, could sour relations with my Hawaiian friends.”

When he had first come to

Hawai’i, he was accepted at the beach, welcomed by the Kahanamoku’s and the beach boys, and “treated… like a king.” Even so, he couldn’t shake the fact that he was an outsider and consequently “… they paid no attention to you,” recalled Tom. “You roamed around there, nobody knew you, and it’s a wonderful way to live, when you keep a low profile. Like, nobody’s shootin’ at you, you know? That went on for years, and it’s just like, I got interested in their sports, surfing and paddling, and managed to build a little better board than they had, and beat them in their contests. And then they began to look at you. There’s something we don’t like, and that was the end of the real good days.”

It may have been the end of the “real good days” for Tom in the Islands, but he still had many good Hawaiian days to come. He would continue his love affair with the Hawaiian Islands– specifically O’ahu – for another 25 years.

Despite the bad feelings surrounding Tom Blake’s wins at the Hawaiian Surfboard Championships 1929-31, other surfboard shapers began experimenting with the chambered hollow board concept. “Imagination of design,” Sam Reid remembered, “ran riot.”

Duke Kahanamoku gave Tom high credit and respect for his contributions. “Blond Tom Blake... was a

haole who accepted the challenge,” related Duke to his biographer Joseph Brennan in their 1968 book

World of Surfing, “and proved to be one of the finest board men to walk the beach. Daring and imaginative he always was. He, like myself, was driven with the urge to experiment.” Addressing Blake’s hollow racing paddleboard, Duke acknowledged that, “He was the one who first built and introduced the paddleboard – a big hollow surfing craft that was simple to paddle and picked up waves easily but was difficult to turn. It had straight rails, a semi-pointed tail, and laminated wood for the deck. For its purpose it was tops.”

Duke’s shaping of a hollow made Tom unabashedly proud. He later wrote: “Duke Kahanamoku built his great 16-foot hollow redwood board along about the same time. He is an excellent craftsman and shapes the lines and balance of his boards with the eye; he detects its irregularities by touch of the hand.

“I feel, however,” Blake added in deference to the Father of Modern Surfing, “that Duke has some appreciation of the old museum boards and from his wide experience in surfriding and his constructive turn of mind would have eventually duplicated them, regardless of precedent.”

Duke’s Blake-inspired design, shaped around 1930, was a 16 footer, made of koa wood, weighed 114 pounds, and was designed after the ancient Hawaiian

olo board, as Blake’s had been.

“With his rare expertise and outstanding strength,” Joseph Brennan wrote, “Duke handled it well in booming surfs. He used to defend his giant board and kid fellow surfers with, ‘Don’t sweat the small stuff. Reason? Because it’s small stuff.’”

After Tom’s win at the Ala Wai, some surfboard and paddleboard builders who had not gone hollow began “using alternating strips of laminated pine or redwood, instead of one or several planks of the same wood,” historians Finney and Houston noted, obviously influenced by Blake’s direction to lessen the weight. “These striped boards combined the strength of pine with the light weight of redwood and were believed to be more functional as well as more attractive. About this time lightweight balsa boards were… tried, but were dismissed as too light and fragile for practical use.”

The 10 foot redwood plank that Duke and the early Waikiki surfers had ridden since shortly after the beginning of the century had been “in vogue until 1924,” Duke recalled, “when Lorrin Thurston, one of Hawaii’s most enthusiastic surf riders, appeared with a twelve-foot board. To Thurston also goes the credit of introducing the balsa wood board in 1926. It was really a revival of the wili wili boards used by the old Hawaiian chiefs except for design. The ten to twelve-foot boards were used exclusively until 1929 when I built [after Tom Blake] a successful sixteen-foot board, which is handled quite the same as the old Hawaiian boards, and I feel sure will put surf riding on much the same scale as it was before the white man came.”

In the progression of the hollow boards’ evolution, Step One (1928) had been the almost accidental use of drilled holes filled in to make tiny air pockets. Step Two (1929) saw the implementation of full hollow chambers. Step Three came in 1932 with Blake’s use of the transversely braced hollow hull. By using ribs for strength, much as in an airplane wing, Tom brought the weight of the hollow boards down even further. It is not definitively known for sure, but it is probable that Tom’s friendship with aviator Gerard Vultee influenced him in this further development of the hollow board. At any rate, the result of this design was a strong 40-to-70 pound board, depending on length.

A final refinement to the Blake hollow board would not occur until the end of the decade, when the board rails began to be rounded. Initially, Tom’s hollows were built with 90-degree flat-sided rails. Whitewater would catch these and easily knock a board right out from under a rider, sending him or her sideways. With the rounded rail, which was an original component to the traditional Hawaiian boards, water could move over and under the board with much less resistance.

After 1932, the Blake hollow surfboard and paddleboard spread worldwide – from as far away as

Great Britainand

Brazil and even

Hong Kong. Although it would be years after Blake’s death that true dynamic hollow surfboards could outperform against solid wooden boards and even foam and fiberglass boards, it did not take long for the hollow paddleboard to become an essential rescue device in oceans, rivers, and lakes. As evidence of this, in the later half of the 1930s, the hollow paddle rescue board was adopted by the Pacific Coast Lifesaving Corps and used by the American Red Cross National Aquatic Schools for instruction. Today, the rescue paddleboard can be found on almost any ocean beach protected by lifeguards.

As for the hollow surfboard, it is significant to note that today, many of the more advanced epoxy boards are of hollow construction. While using technology undreamed of by Blake, they are nevertheless take-offs on his original hollow board concept.

Wells, Lana. Sunny Memories – Australians at the Seaside, ©1982, pages 157-158. 1982. Greenhouse Publications Pty Ltd., 385 - 387 Bridge Road, Richmond, Victoria 3126. Hardcover, 184 pages, black and white photographs, Chronology of Events. Geoff Cater wrote: “Expansive overview of Australian beach culture and history, starting with James Cook’s description of ‘indians’ (aborigines) bathing in 1776. Surfcraft in Chapter 12. ‘Riding the Waves’ is interesting; particularly the sections on Isabel Letham (sic) page 156, Grace Smith Wootton (1915 Victorian surfer) page 157 and C.J. (‘Snow’) McAllister page 159; but does not progress much past 1970. The Chronology is useful, but note the 1964 World Contest at Manly is listed as 1960. Photographic Highlights:“Andrew ‘Boy’ Charlton and Snow McAllister, both wearing V shorts over their bathing suits, with their boards at Manly, 1926” pages 88-89,‘St Kilda Life Saving Club Member with a surfboard ... Manly’ circa 1929, page 151,‘Grace Wootton Smith’ page 157. See image of Grace Smith Wooton and Win Harrison, Point Lonsdale, Victoria, circa 1916, Wells page 157.” Brawley, Sean. Vigilant and Victorious - A Community History of the Collaroy Surf Life Saving Club 1911 – 1995, ©1995, pages 33-34. Collaroy Surf Life Saving Club Inc., PO Box 18CllaroyBeach2097. Australia. Hard cover, 410 pages, black and white photographs, Notes, Office Bearers, Bronze Medallions, Subject Index, Name Index. Geoff Cater wrote: “Highly detailed account of one of Sydney’s first Surf Life Saving clubs and the growth of its community.Although boardriding plays only a small part of such an expansive work, the significant details recorded here are not available from any other source.” Wells, p. 153.