↧

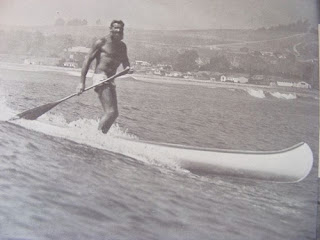

Corona del Mar 1930s

↧

1930s: Mid-Decade

7. Mid-1930s

By the mid-1930s, “the surf world remained for the most part tri-cornered – practiced in Australia, Hawaii, and California by less than three thousand people total,” wrote surf writer Matt Warshaw in The History of Surfing, “— and each region was separated from the others by layers of cultural and geographic insulation… Over the previous thirty-five years, maybe a dozen surfers had circulated between California and Hawaii Australia to Hawaii , or vice versa, and surf travel between California and Australia

Waikiki became the place of pilgrimage for California Australia

Often overlooked in most discussions on the spread of surfing during the first several decades of the Twentieth Century, is the contribution and importance of the body board, what long ago Hawaiians used to call the kioe. Even before the 1930s, there were people riding wooden “belly boards” two-to-four feet long in Australia , California , the East Coast of the United States , and in England

Florida

Beyond wooden body boards, the development of United States East Coast surfing was spearheaded by Tom Blake’s invention of the hollow board. By the mid-1930s, his influence stretched from Oahu to Southern California clear to

Of his influence in Florida , Tom recalled: “Florida

Dudley and Bill Whitman, two of Florida ’s first known native surfers, began on belly boards at Miami Beach Hawaii ...”[3]While touring in Florida

By the 1930s, Mainland USA surfing was no longer confined to California New Jersey and New York , and Tom’s presence in the state, surfing got underway in Florida Florida Miami Beach Florida

“We knew Tom from about 1932 or ‘3 for the rest of his life, virtually,” said Dudley . “Last few years I kind of lost track of him, but we used to exchange correspondence occasionally.”[8]

“I always thought of Tom as a person about 35 years old, or something like that,” Dudley Whitman stated, philosophically. “And, of course, he did age as we all do, but he always kept his youthful appearance. The amazing thing was that, finishing this particular board off, it was outmoded just before it was finished! So, very shortly after meeting Tom, my brother Bill built the first hollow board ever in Florida

“Well, it’s been documented, I think,” Dudley Whitman said of the first surfers in Florida Virginia Beach

“So, my brother Bill built his board, and then I told you about myself building my solid board. So, my brother Bill built the first Hawaiian surfboard ever built in Florida Florida Hawaii

“Well, of course, Tom was physically fit, a pretty handsome man, and as a person that knew him, he was a little different than a lot of surfers that you know,” Dudley said of Tom Blake and his early impressions of him. “Some people might say, or like to think, that maybe he was a hippie-type or something. No. He was a type of person of his own kind. He was always immaculately dressed with excellent clothes, excellent taste, and never far-out... He always, always presented well; not a rundown-looking, sloppy bum like you and I know some surfers degenerated to.”[11]

“Miami Beach Collins Avenue Thirty-second Street Collins Avenue Miami Beach Miami Beach Miami Beach South America .”[12]

Dudley Whitman said of the surf spots back then: “We probably surfed more up in Daytona than in Miami Beach University of Florida

“I was surfing before the Whitman brothers came up from Miami and joined us in the mid-’30s,” recalled Gauldin Reed, of the earliest days of surfing Daytona Beach

“Nobody knew what we were doing,” Dudley admitted. “We carried our boards on the cars, these hollow Tom Blake boards that were 12 feet long, and people just didn’t understand it. Daytona was the focal point in Florida

The hollow boards they built were “rounded… off a little bit more like the modern boards of today. They were put together with wooden pegs instead of screws like everybody else had.”[16]The wooden pegs created quite a stir at Waikiki when they were first seen. “Well, that’s a pretty good story,” Dudley Whitman declared when asked about his connection with the Outrigger Canoe Club and the story of the wooden pegs. “I don’t know how long we had known Tom; maybe for a year or two. Yes, at least that; maybe more. Definitely more. We were going to Hawaii Hawaii Waikiki . So, after Duke had shoosed us, why we immediately started to unpack our boards that were wrapped up in canvas. After they saw our boards, maybe ten or twenty Hawaiian surfers gathered around. By the time we got them unpacked, there must have been at least a hundred or a hundred and fifty standing around. They took us to the Outrigger Canoe Club, gave us the racks of honor! I’ve been a member of the Outrigger Canoe Club ever since.”[17]

“My brother Bill’s probably been to Hawaii

“This one that I built, that we have in the museum,” Dudley Whitman recalled of the first surfboard he ever built, “The board that I was telling you about, about 1958 or 1962 I gave it to a doctor friend, or loaned it to him so he could train to go to Hawaii with us. Of course, we were riding modern boards like the type you have today; particularly Hobie boards… [Dudley ’s original board that he loaned was] run over with a car, [so] I built another one. I loaned it to this friend of mine, Dr. Bradley, so he could condition himself for a surf safari we had in Hawaii

“I said, ‘Well, I’m throwing it away.’

“He said, ‘You can’t; it’s historic.’

“I said, ‘Oh, yes, I can. It’s a piece of junk.’

“So, he took it to Columbia , South Carolina

Stand-up surfing and body boarding were not the only water sports the early Florida Riviera Riviera Florida United States Dudley , we’re going to have a water show. We want you to be in it.’ And I said okay. I think I was in college at the time; I’m not sure. Or, I was in high school. And he said, ‘We want you to do the single ski act.’ And I said okay.

“It happens that the ski that I had built from scratch, laminating it and everything else, was pretty much like the ones that were built in Europe , but the only skis that were made in this country actually weren’t stable. So, if a person did any single skiing, they probably went for 500 or 800 feet and invariably they’d fall off… it just wasn’t real satisfactory. Because of that, I practiced up and I never rode two skis again. So, it took about three, four years to get my friends to change over. And [one day] Bruce Parker writes me a letter and calls me on the telephone, both. He says, ‘Dudley , please stop that single skiing. We don’t need any one-legged skiers.’ Well, that’s slalom skiing as it is today. And one of our group – a younger brother of one of my close friends, who’s an expert skier – his brother went up to Cypress Gardens

In “Surfer, horticulturist William Whitman dies,” David Smiley of the Miami Herald wrote: “A pioneering U.S. East Coast surfer (and horticulturist) has left us. Dudley Whitman’s brother Bill has passed on at age 92.

“The surfboard Bill Whitman built in 1932, the first of its kind in Florida Bal Harbour United States and donating more than $5 million to Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

“William ‘Bill’ Francis Whitman Jr. died in his home… He was born June 30, 1914 in Chicago , but as a boy the family moved to an oceanfront home in Miami Beach Florida

“‘He was probably one of the greatest underwater men that ever lived,’ said brother Stanley Whitman. Added brother Dudley: ‘He was more fish than man.’ An example of the brothers’ 80-plus pound surfboards can be seen in their private museum at the Whitman-owned Bal Harbour

“On their trips to the Pacific after World War II, the brothers learned new trades, including spearfishing, which they introduced to the East Coast and Caribbean , Dudley Whitman said. In 1951, Bill Whitman wanted to show friends back in South Florida a glimpse of the South Pacific, so he created the first underwater camera and began shooting film below the surface, Dudley said. Early films earned the brothers nominations for Academy Awards. They sold some of the scenes they shot to filmmakers for use in the 1952 documentary ‘The Sea Around Us.’ The film won an Oscar. “We won the academy award and we weren’t even in the business,” Dudley Whitman said.

“Despite the accolades, Whitman was possibly best known for his expertise and accomplishments in horticulture. He devoted himself to bringing back to South Florida many of the exotic fruit species he found in the South Pacific. He found the sand and marl in his own backyard unfit to nurture the fragile plant life, so he had 600 truckloads of rich acidic soil taken from Greynolds Park area and dumped in his Bal Harbour United States

“In 1999, Whitman donated $1 million to Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden University of Florida ’s College of Agriculture

David Karp, of the New York Times wrote in “Bill Whitman, 92, Is Dead; Scoured the Earth for Rare Fruit,” that “William F. Whitman Jr., a self-taught horticulturist who became renowned for collecting rare tropical fruits from around the world and popularizing them in the United States, died… at his home in Bal Harbour, Fla. He was 92.

“Mr. Whitman, who had suffered strokes and a heart attack, died in his sleep, his wife, Angela, said. Among rare-fruit devotees, Bill Whitman, as he was known, was hailed as the only person to have coaxed a mangosteen tree into bearing fruit outdoors in the continental United States Southeast Asia , mangosteen is notoriously finicky and cold-sensitive. That did not deter Mr. Whitman, whose garden is propitiously situated between Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean , minimizing the danger of catastrophic freezes. (Mangosteen is the most prominent of the exotic ‘superfruits’ like goji and noni, which are made into high-priced beverages from imported purées.)

“Mr. Whitman managed to cultivate other fastidiously tropical species like rambutan and langsat, and he was recognized as the first in the United States Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables , Fla. Florida

“William Francis Whitman Jr. was born in 1914 in Chicago, a son of William Sr. and Leona Whitman. His father owned a printing company in Chicago and added to his fortune by developing real estate in Miami Florida Tahiti , where he became enchanted by the fruit. Mr. Whitman was a founder of the Rare Fruit Council International, based in Miami Florida

Jordan Kahn of the Daytona Beach News-Journal wrote a fine history of the early days of surfing at Daytona and Miami Beaches Daytona Beach become Florida

“There is a grainy photograph of surfers posing near the Main Street Pier [in Daytona Beach Florida

“From a campsite on the beach a few blocks south of the pier, three brothers waded through the sea foam, and surfing in this city began. “People didn’t know what a surfboard was, and for years they didn’t know what we were doing,” said Dudley Whitman, one of those brothers. The puzzling sight of these three brothers from Miami Beach Daytona Beach Shores Stetson University

“None of the men in that 1938 photo was the first person known to surf Florida Hawaii

[Hawaiian] “Duke Kahanamoku... was famed as much as a surfer as for being an Olympics sensation, setting world records and winning three gold medals in the 1912 and 1920 games. It was Kahanamoku who inspired Blake to take up surfing. When Kahanamoku traveled to swim meets, he saved surfing from disappearing by giving the surf exhibitions for which he is now renowned as the ‘Johnny Appleseed’ of modern surfing. Kahanamoku told his biographer that by 1900, western colonization had so completely stamped out native Hawaiian culture that ‘surfing had totally disappeared throughout the islands except for a few isolated spots… and even there only a handful of men took boards into the sea.’ It is surfing’s narrow escape through this historic bottleneck that gives it a lineage like a family tree. Ancient Hawaiians are surfing’s roots. Kahanamoku is the trunk. And surfing’s genesis in Daytona Beach

“Whitman said lifeguards visiting Miami from Virginia Beach Miami Beach Florida

“These brothers’ surfing experiments may have begun in Miami , but they did most of their actual wave riding in Daytona Beach as students at the University of Florida in Gainesville Florida

“And among the surfers in that 1938 photo are Paul Hart, a lifeguard examiner for the Red Cross, and Donald Gunn and Dick Every, who are both wearing the wool tank-top uniforms of the day for Daytona Beach lifeguards. Every even remembers a picture of Blake surfing in Daytona Beach Harvey Street

“I remember seeing Dudley driving into town in a fancy convertible with surfboards towed behind it,” said Every, now 85. “My brother and I decided to build boards like them.” Gaulden Reed said in an interview before his death in November [2007] at 89 that people started making Blake-style boards in Seabreeze and Mainland high school shop classes. Bill Wohlhuter, the owner of Port Orange Seafood today, said he built his board from plans he got from Every’s brother, Don. ‘I once mounted a 1 1/2-horsepower Water Witch outboard on that board,” Wohlhuter said. ‘I steered the tiller with my foot!’ Many of these men – including the three Whitmans – are in the photo, preserved by the surfing hall of fame in Cocoa Beach , the Halifax Historical Museum in Daytona Beach and the Whitman family museum in Miami Florida

“By today’s standards though, those boards are closer to boats. ‘They were kind of like a freight train,’ Whitman said. ‘They were very much faster for paddling, slow to get started of course, but probably faster than you could paddle a canoe once you got going. And you could catch big waves much farther out.’ After hurricanes, to make it past the onrush of whitewater, Reed said he used to throw his board off the pier and dive in. ‘During the hurricane season, you could catch some pretty good-sized ones, maybe 7- , 8- , 9-foot waves that were breaking out there beyond the pier,’ Nelson said. ‘You’d have to really walk the board. You’d catch the wave and you’d have to walk about four or five feet to keep the nose down and then walk it back and forth to keep it going.’

“They stuck their hands in the water like oars to prod those big boards into turns. ‘To be a cool cat and get the girls,’ Nelson said, ‘you had to lean over with your hand to steer it.’ The real hot dog move was shooting the pier, surfing through the pilings from one side to the other. ‘I almost lost a kneecap trying to do it,’ Nelson said.[26]

“When some of Daytona Beach ’s surfers made their first pilgrimage to the sport’s birthplace, these Florida Waikiki ... They were beautifully crafted; one made with mahogany and brass screws. Blake had given the Whitmans a letter of introduction to the Outrigger Canoe Club, the first surfing club.

“‘We were just kids and we showed it to Duke,’ Whitman said. ‘But he didn’t really have time for a couple of haole (Hawaiian slang for mainland outsiders) boys. So we went ahead and unwrapped our surfboards. People gathered around to watch us unpack and when the Hawaiians saw our surfboards, they gave us surf racks of honor.” The Whitmans were made club members and they surfed next to Kahanamoku. Reed also flew [probably travelled by steamship, as commercial aviation was still in its infancy] to Hawaii Daytona Beach

“A nucleus of roughly 45 Daytona Beach Daytona Beach Mainland High School

“When Every returned home from the war in ‘45, he said, ‘there was no surfing at all.’ Tony Sasso, a longtime director of the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame Museum in Cocoa Beach Daytona Beach Daytona Beach ’s claim as Florida

“By 1958, foam and fiberglass surfboards had transformed the sport. Richard Brown of Daytona Beach Seabreeze High School

“What has generally been remembered as Florida Hollywood Daytona Plaza

“... Richard remembers one of the best days of surfing he ever had was after a hurricane in 1964. ‘I came home from Gainesville California

“Is it possible that boogie boarders were the first wave riders in Florida Miami Daytona Beach

“How this more basic wave sport made it to Florida Hawaii or cities in California

“... [At] the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame Museum in Cocoa Beach and the Halifax Daytona Beach Carlisle ‘Boop’ Odum, Earnest Johnson, George Boone and George Jeffcoat.

“Plus there are two surfers from the 1938 photos that remain unidentified. That’s a total of 29 surfers. James Nelson remembers the photo as taking place after the event and after some of the competitors had already left. And in the photo, only 16 surfers are shown, but Dudley Whitman is wearing a No. 24. Dick Every said there were probably about 10 or 15 more surfers in the area who didn’t come to the event, giving 1938 Daytona Beach a rough estimate of 40 to 45 surfers. ‘There was nobody from New Smyrna surfing and I don’t recall anybody from Cocoa

“‘(Hart) was in the same fraternity we were in, in Gainesville Main Street Stetson University Daytona Beach Flagler Beach Akron , Ohio

Back in the beginning years of Floridian surfing, just after it got underway, Tom Blake returned to lifeguard at the Roman Pools, located on 23rd Street Miami California and Florida

In Hawaiian Surfboard, he mentioned briefly a trip to the Bahamas with his surfboard along; quite probably the first surf safari to the Bahamas : “In a seaplane, (Pan American) trip from Nassau Gulf Stream , I could have maintained the two pilots, steward, three passengers and myself from sinking for many hours, or until help came.”[34]Dudley Whitman said they also “surfed the island of Eleuthera

Reviews of Tom’s book, published in 1935, reference his previously working in New York – even New York City Florida New York , since the time he worked in the carnival at Jones Beach Florida Miami New York

Tom travelled to Long Island , New York New York City Jones Beach and credits “Mullahey of Honolulu and Valley Stream , N.Y. ” with making lifeguards at Jones Beach

“I went up there,” Tom continued of his New York Islands , again, for some surfing.”[38]

Long Beach

Back in California, in summer 1933, at one of the most popular surf beaches at the time – Long Beach– City Ordinance No. C-1195 went into effect, restricting surfboard riders to certain areas of the beach. If surfers failed to obey, it was possible that they could be fined $500 and put in jail for six months. The June 16th edition of the Press-Telegram gave the lowdown:

“An emergency ordinance, proposed by the Municipal Lifeguards… [has] become City Ordinance No. C-1195. Henceforth, timorous bathers need not dive in terror to the bottom of the sea in hope of avoiding being cut in twain by a speeding Hawaiian surfboard. The surfboard riders either will mind the new P’s and Q’s or will go to jail.

“Certain lanes of the surf will be reserved for bathing, and other lanes will be legal highways for riders of the booming wave. The maximum penalty for offense is a fine of $500, six months in jail, or both.”[39]

At the beginning of the following summer, the Long Beach

“For beginners there are always plenty of little crumble waves, easy to ride on a two-bit surfboard. The experts ignore such ripples and ignore such surfboards; they ride a ‘comber’ or none at all, and they use either an Hawaiian board or none at all.

“There are several approved methods of wave riding. The simplest for the beginner is to repose oneself upon a thin five-foot plank and to place oneself, plant and all in the path of a wave. With fair luck the wave then will carry one, plank and all, on a speedy scenic voyage to the beach.

“The second variety of wave riding in the board class is much more spectacular. It requires strength, courage and skill. Furthermore, the participant may crack his skull or break his neck, before reaching the safe degree of expertness. The rider paddles seaward on a surfboard nearly twice his own length and equal to his own weight. Away out in the breaker line he about-faces and waits for a ‘big one.’ Pretty soon a toppling wall of green sea water approaches. The rider paddles; the wall scoops him up, board and all, almost to the point where board and rider would spill. Precariously he rights the board and as it is driven shoreward in front of the breaker’s crest he stands upright, aloof, conqueror of board and breaker. Or else, with a precipitous and ungraceful leap, he loses balance and disappears in the water.

“Of body surfing, as the lifeguards call it, there are two varieties. In one, the arms are extended beachward while the rider moves along in the lather of a wave. This type is juvenile; this type is taboo among the tanned gentry of many beach seasons. They prefer the second and more spectacular way of body surfing.

“This latter way is to clamp the arms against the sides, push the shoulders forward and stick the head down, and to ride the wave face-downward. The bathers who survive the rigors of learning this are in heavy surf become expert at ‘taking the drop’ with a crashing breaker and riding part and parcel with it until it casts itself upon the sand. Occasionally on the swift shoreward voyage they take a breath by raising the head, with jaw pugnaciously forward; barracuda-fashion.

“The experts in advanced surf riding have a right to strut on the beach. They have challenged the ocean’s mightiest breakers and have looked Old Man Neptune squarely in the eye.”[40]

Two years later, in September 1936, the Long Beach

“‘Hold the surf board in a horizontal position, the end against the middle of your body. Turn a little cornerwise to the breakers, so that you can see the rolling water over your shoulder. When the wave gets to you make a swing straight for the shore. Lay the board flat on the water and slip both hands to the center of the board at full arms length.’

“It’s Stephen ‘Steve’ Skinner speaking, and Steve should know. He not only rides a surfboard himself, but has taught a thousands others to do the same. Friendly, smiling and burned a mahogany color by the sun, Steve spends his spare time between Silver Spray Pier and Rainbow Pier swimming, riding a surf board, teaching others to ride, chatting with tourists. He is a one-man Chamber of Commerce, teaching enjoyment of water sports and making friends for the city.

“‘When I first came to the coast from Wichita , Kansas

In 1937, what Long Beach lifeguards and city fathers had feared might happen finally did, only it was not an injury caused to a bather by a surfer but rather self-inflicted upon the wave rider. The Press-Telegram reported: “Woman, Hurt by Surfboard July 5, Dies of Injury: Fatality First of Kind Ever Recorded in History of Beach.”

“Mrs. Phyllis Hines, 19, whose riding of breakers here July 5 came to an abrupt and painful stop when her own surfboard jabbed her in the abdomen. She died last night from effects of the blow.

“While the autopsy surgeon’s report was awaited today lifeguards here said that the young woman’s death was the first surfboard fatality of which they have heard. ‘Sometimes a bather has received an injury from a surfboard, usually because he tried to lie too far forward on the board, forcing it into a nose dive under water,” Lieutenant Henry P. Coleman of the Municipal Lifeguards said this morning. ‘Usually the injury is only a bruise or a bump on the head.’ A city ordinance requires surfboard riders to stay away from the surf immediately in front of lifeguard stations, where the boards might imperil swimmers.

“Police reports of the accident to Mrs. Hines indicate that a wave drove her own surfboard against her while she was in the surf with hundreds of other bathers.”[42]

The following year, the local paper gave a rundown of contest results from the “Southern California surfboard relay championship”:

“Surfboard riding, ancient sport of South Sea Islanders, gave a crowd of several thousand beach visitors a thrilling show here yesterday in Southern California championship events in the Salute to the States water circus beside Rainbow Pier.

“More than thirty expert surfers competed in the races. They represented surfing clubs of several beach cities. Their spectacular rides and frequent spills proved to be the most popular entertainment on the 4 1/2-hour water circus program. Five husky swimmers of the Manhattan Beach Surfing Club won the Southern California surfboard relay championship from the Hermosa Beach Surfing Club. The Venice Paddleboard Club finished third. Each member of a competing team raced from the beach to a marker a quarter-mile offshore and returned to the beach riding on a breaker, passing his surfboard to the next member of his team.”[43]

Following this regional paddleboard contest, Long Beach United States America

The main event started with a half-mile paddleboard race through the surf. Women as well as men competed. It was broadcast live over radio station KFOX while 20,000 people crowded onto Rainbow and Silver Spray piers and the beach in front of the Pike to view 140 competitors. Pete Peterson and Mary Ann Hawkins of the Del Mar Surfing Club won in the national paddleboard division.

In conjunction with the paddle boarding event, there was also a surfing competition scheduled. However, lack of heavy surf postponed the surf contest until December 11, 1938. Not wanting to disappoint the crowd who had come to see them perform and the radio audience who were listening, the surfers held a trial open surfing event, with John Olson of Long Beach winning the competition, James McGrew of Beverly Hills placing second and Denny Watson of Venice third.[44]

“Preston Peterson and Miss Mary Ann Hawkins of Del Mar Surfing Club yesterday were crowned national paddle board champions,” reported the Long Beach Press-Telegram,“in the first annual national surfing and paddle board contest at Long Beach

“Lack of a heavy surf made necessary a postponement of competition in the surf riding events and the highly anticipated initial interclub clash for possession of the Dick Loynes perpetual team trophy until December 11.

“Riding the small waves, John Olson of Long Beach won the open surfing event with James McGrew of Beverly Hills Long Beach

40,000 onlookers watched sixty-five surfers compete in team and individual competitions on that cold December day in 1938. The Santa Ana Band led the participants, whose boards ranged in length from eleven to eighteen feet, to the edge of the surf between Rainbow and Silver Spray Piers where the water temperature was 52 degrees. Newsreel, magazine and newspaper photographers were also there taking pictures of the event.

The Press-Telegram reported on the following day:

“Forty thousand onlookers yesterday watched one of the most thrilling aquatic demonstrations ever staged when nature provided thundering rollers for the third annual Mid-winter Swim coupled with the National Surfing Champions.

“Postponed from a month ago, the National Surfing Championships provided the greatest action, with sixty-five surf riders participating. The Manhattan Surfing Club won the 44-inch silver perpetual team cup. The Venice Surfing Club placed second, Santa Monica third, Palos Verdes Surfriders Club fourth, and the Del Venice , with Jim Kerwin of Manhattan Beach coming in second, and Don Campbell also of Manhattan Beach Manhattan Beach , fifth place; Kenneth Beck, Venice , sixth; Bob Reinhard and John Lind of Long Beach

So successful was this first national Surfing and Paddleboard Championships, a second was held the following year off Rainbow Pier – again during the winter swell season – on December 3, 1939.

“A three-man team representing the Hermosa Beach Surfing Club yesterday won the Dick Loynes perpetual trophy emblematic of the national surfing championship in an event in the fog-shrouded waters off Rainbow Pier.

“Booming out of the fog blanket on the crests of curling breakers that saturated onlookers, the Hermosa Beach men nosed out the defending trophy holders of Manhattan Beach Long Beach

“Individual surfing honors went to Long Beach Surfing Club members John Olsen who finished first, Alvin Bixler, second, and Bob Rhienhardt, forth. Gene Smith of Hawaii

The second was the last. There would never again be another national surf contest held in Long Beach United States Long Beach breakwater was extendedduring the war when the U.S. Navy came to Terminal Island Long Beach

San Diego

“There’s a good chance Ralph Noisat caught the first wave in

De Wyze wrote that “… as he wasn’t a man to brag, his pioneering role might have been lost were it not for his board. He made it himself when he was a boy, and it was still in the Noisat family home in 1998 when Ralph’s daughter, Margie Chamberlain, was preparing to sell the Mission Hills residence. Chamberlain realized the heavy wooden board might have historic value… her father’s maternal grandfather worked on the construction of the Pioneer Sugar Mill in Lahaina, Maui . Her father’s mother spent at least part of her childhood there, before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, marrying, and having [her father] Ralph in 1896. From what her father later told her, Chamberlain got the impression he was close to his grandfather; he may have even visited him in Hawaii

Although Ralph Noisat’s daughter didn’t know “how her father came to make the seven-foot-long, square-tailed board, ‘He always talked about the wood being koa,’ she says. She has the impression he may have surfed on it in Northern California before 1910, the year he and his mother moved to San Diego San Diego High School

“Before he reached his 18th birthday in 1914, Noisat enlisted in the Navy, embarking on a military career that would last 30 years. Chances are he wasn’t here when one of the most famous surfers in the world arrived. George Freeth, born in Oahu in 1883, was the son of an Englishman and a half-Hawaiian woman. A champion swimmer and high diver, Freeth taught himself the ancient Hawaiian art of riding waves, a skill that by the end of the 19th Century had almost disappeared from the islands. By 1907 he was so adept he caught the eye of writer and travel adventurer Jack London, who later described Freeth’s aquatic prowess in The Cruise of the Snark. London was among those who provided letters of introduction to the young Hawaiian as he prepared to sail to California

“Less than three weeks after departing Oahu (on July 3, 1907), Freeth was surfing at Venice Beach California Santa Cruz Surfing Museum San Mateo surfed at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River in Santa Cruz Venice and Redondo Beach Venice Los Angeles County , Long Beach , and San Diego

“For all the acclaim, Freeth struggled to make a living. He got a break in 1915 when the moneyed and well-connected San Diego Rowing Club asked him to coach the club’s swim team. Freeth took the job, and it seems likely he would have surfed in San Diego [at that time] at least in the summer months, when to earn extra money he taught swimming in Coronado. By May 1918, after 13 men died in a single day in rip currents off Ocean Beach Ocean Beach

“That was around 1916 or 1917, according to local amateur surfing historian John Elwell. Elwell says [Duke] Kahanamoku surfed the OB Pier, and when he did, he asked a teenaged lifeguard named Charlie Wright if he could store his board in Wright’s beach shack. Elwell, who interviewed Wright a few years before his death in 1994, says Wright encouraged Kahanamoku to use the shack but asked if he might try the board. ‘So Charlie surfed the board and also got the dimensions and later copied it,’ Elwell says.[51]

“Wright, who was something of a showman as well as an entrepreneur, was putting on surfing demonstrations at special events. The California Surf Museum has one photograph of Wright surfing on New Year’s Eve of 1925 next to the Crystal Pier in Pacific Beach

“But by the late 1920s, Wright wasn’t using his board for much besides the occasional exhibition. Emil Sigler says he found it near the Mission Beach lifeguard station when he went there the day after his arrival in San Diego

“Born in San Francisco Queenstown Court Mission Beach Ocean Beach , claiming that the outflow from Mission Bay Pacific Beach Mission Beach

“Sigler will tell you he was the first serious local surfer, but Lloyd Baker dismisses that claim with a snort. Sigler ‘surfed a little bit,’ Baker acknowledges, ‘but he was not very agile. Not that he wasn’t strong and not that he couldn’t have become a better surfer, but he and Don Pritchard and Dempsey Holder [two other early surfers] were never, ever stylists. They went out and tried, but when they got up it was like you never thought they were going to last for more than 20 feet before they fell off or something.’[54]

“Baker says he and his pal Dorian Paskowitz and a handful of other teenagers from Point Loma and La Jolla were the first true San Diego

“Born in San Diego , Baker and his family moved around California in his early childhood, but in 1934, when Lloyd was 13, they settled into a house at Portsmouth Court Mission Beach

“School was Point Loma High, which they reached by riding the streetcar that ran south on Mission Boulevard Ocean Beach Mission Bay Hawaii and become fascinated by the ancient Hawaiian boards in Honolulu ’s Bishop Museum Mission Bay

“Besides being unwieldy, the boards ‘were a pain in the ass, because as soon as they got just a little warped or they got in the sunshine or whatever, why, they started leaking,’ Baker says. When a fellow named Pete Peterson moved from Hawaii to San Diego, where he got a job at the Mission Beach Plunge, he brought with him a couple of square-tailed solid-wood Hawaiian boards, and the boys studied these with interest. About the same time, they learned about boards that promised to work better than paddleboards or Hawaiian planks.[57]

In the early-to-mid 1930s, “a Los Angeles-based manufacturer of prefabricated homes started building surfboards as a sideline. Although the company used solid redwood at first, it later began importing lightweight balsa from South America for use in both the home-building and surfboard-manufacturing businesses. The balsa ‘was beautiful stuff!’ Baker recalls. ‘They had it all milled, and it was very pretty.’ But a surfer couldn’t simply order a finished board. He had to request that a block of wood be manufactured to the shape and dimensions he specified. ‘They’d put it together in any configuration you want,’ Baker says. ‘You could actually go through their bins and pick out the pieces you were going to have them glue up.’ Some pieces were harder, some softer; they also varied in weight. ‘You could pick them out so the board balanced. You’d pick out redwood pieces with pretty grains of wood.’ If you wanted a “runner” of redwood glued down the middle of the board to stiffen it or along the sides (the rails) or tip (the nose) to protect the softer wood, you could order that too. You drove up to L.A.

“Baker became renowned for his skill at shaping the Pacific Systems Homes boards. Today he downplays his ability; he says he wasn’t great compared to subsequent generations of shapers. But for a few years in the late 1930s, he worked on probably 40 or 50 boards. Baker worked on boards for Paskowitz and for the small gang of Ocean Beach and La Jolla boys who had started surfing, as well as others. He did it for free. ‘We were happy to do the work and pass the board on to somebody that would use it.’ Because they were lighter, weighing 45 to 65 pounds, the balsa/redwood boards were more responsive in the water, and with the addition of a fin (introduced by Tom Blake in 1935), they became more maneuverable.[59]

“Kimball Daun, one of the Ocean Beach Mission Bay

“Their first attempt at following his example involved a paddleboard owned by an older teenager named Bob Sterling. ‘He would take it out on the ocean, usually on calm days, and paddle round on it.’ Sterling Ocean Beach

“They couldn’t steer at all, but they had fun on Sterling ’s board, Daun says, until the day one of them caught a good-sized wave and nosed in hard enough to hit the bottom. ‘All of a sudden, the board was just sunk, which was unusual.’ When they got it onto the sand, they realized ‘four feet of the plywood bottom of the board had peeled off and was just hanging under it. We thought, “Oh my God, this is ruined.”‘ Sterling Green Street

“A bit of larceny enabled them to get a board of their own. This happened one night when the boys were walking home from the high school. ‘Out around Coronado Avenue Ocean Beach

“Somehow that worked. Three-quarters of an inch thick, the boards were far too thin to be made into a solid surfboard, so Daun and Malcolm set about building another box with cross-members. For this they needed screws and plywood, which cost little – but more than they had. ‘But Skeeter got 20 cents a day for lunch money, which was unheard of for me,’ Daun says. ‘I had my mom make three sandwiches for me, and I’d take two and give Skeeter one. That way he could save his lunch money.’ They earned a bit more from chores. ‘We finally got the board built, and at 11 feet long, it was slow in turning, just like all big boards. But for a hollow board made at minimal expense, it was easy to catch waves.’[63]

“Daun says he and Malcolm (who died in 1993 after a long career as a teacher, coach, and principal) later graduated to boards fabricated from the Pacific Systems Homes balsa/redwood blanks and shaped by Lloyd Baker. So did three other Ocean Beach

“The weight of the boards limited the choices of where these first hard-core surfers surfed. ‘See, in those days, those boards were nose-heavy,’ explains Bill (“Hadji”) Hein, who by the late 1930s had joined the small band of regulars at Mission Beach

“Often compared to Waikiki in Hawaii , San Onofre began luring Southern California surfers as early as the 1920s. According to Emil Sigler, the location’s remoteness encouraged some at the all-male gatherings to swim naked, in a day when men wore bathing suits that covered them from neck to knee. By the 1930s, San Onofre was the setting for the Pacific Coast Surfriding Championships, the first organized surfing contests in the world. These were not cutthroat affairs, according to Jane Schmauss, the director of the California Surf Museum in Oceanside Hawaiian Islands spirit.’ San Onofre was too far away for everyday surfing. So was Imperial Beach for all but the few guys who lived there, and most of the time the IB surf wasn’t great anyway, Baker says. But in the winter, when the surf came up at Tijuana Sloughs, ‘Then Dempsey [Holder] would call, and we’d go down.’ It might happen only three times a year, Baker says, ‘usually for three to four days. Then there wouldn’t be any other surf for a month or so. And the beach surf [in Imperial Beach ] wasn’t any different than the beach surf at Mission Beach

“The waves off Sunset Cliffs were excellent year-round, although access to them wasn’t easy. A fellow could make the long paddle south from Ocean Beach

“At Windansea, the reef causes the swell to break abruptly, creating powerful waves that often have a tubular shape. But no one rode Windansea until 1937. One day a young glider pilot named Woody Brown, riding a homemade hollow board, and a handful of other young men from La Jolla ‘found great surf at Bird Rock and Pacific Beach Point, where we rode 20-foot waves, taking off right on the edge of the kelp,’ Brown recalled in a 2000 Surfer’s Journal article. He and his buddies then ventured out at Windansea. After that, Ocean and Mission Beach

“Most, however, considered PB Point ‘the absolute best for us,’ according to Kimball Daun. ‘You always had a long right slide. When the surf was really big, you could actually ride all the way over to Tourmaline.’ As at Sunset Cliffs, access to the water off the headland wasn’t easy. ‘You had to drive up La Jolla Boulevard

“One other way at least a few people reached Tourmaline Beach was via a City of San Diego Mission Beach Tourmaline Beach

“An encounter on that truck resulted in the Ocean Beach OB cohorts. Finally Sigler started the engine to drive back to the lifeguard station. ‘Well, Skeeter and I were going to have to walk down to Old Mission Beach

“Were the Vandals the first San Diego Mission Beach Mission Beach Queenstown Court

Aloha Shirts

One enduring “invention” that came out of the mid-1930s was what we now call the “Aloha Shirt.” As land based attire, it would help define the beach lifestyle that continues today.

The Aloha Shirt was initially thought up in the early 1930s by Chinese merchant Ellery Chun of King-Smith Clothiers and Dry Goods, a store in Waikiki . “Chun began sewing brightly colored shirts for tourists out of old kimono fabrics he had leftover in stock,” describes the Wikipedia. “The Honolulu Advertiser newspaper was quick to coin the term Aloha shirt to describe Chun’s fashionable creation. Chun trademarked the name. The first advertisement in the Honolulu Advertiser for Chun’s Aloha shirt was published on June 28, 1935. Local residents, especially surfers, and tourists descended on Chun’s store and bought every shirt he had. Within years, major designer labels sprung up all over Hawaii

The same year that “Aloha Shirt” became a registered trademark, a surfer named Nat Norfleet Sr. and his partner George Brangier opened an Aloha shirt company called Kahala. “We began like nearly everybody else in the business, not with a pair of shoestrings but with one shoestring between the two of us,” Norfleet Sr. said. “Red McQueen had brought back from the 1932 Olympics in Japan

“The shirts were purchased by local residents, beach boys, surfers and tourists. The first advertisement placed in the Honolulu Advertiser using the words “Aloha Shirt” was on June 28, 1935. With the birth of Rayon in the mid 1920’s, the dazzlingly colored and tropically decorated Hawaiian-Print Aloha shirt became a staple souvenir of cruise ship tourists. Early shirt labels bore names like Musa Shiya, Watamulls, Kamehameha, Kahala, Surfriders, Alfred Shaheen, Duke Kahanamoku, etc. The 1940’s and 1950’s furnish us with a memorable list of personalities depicted wearing Hawaiian-Print Aloha Shirts. Elvis Presley, the undisputed king of rock and roll had many Hawaiian Shirts. Here is an off-the-top-of-my-head, recollection, list of famous people, motion picture and television personalities, politicians and sports celebrities that have been photographed and featured wearing Hawaiian-Print Aloha shirts. Harry S. Truman, our 33rd President loved to wear Aloha Shirts. He was on the cover of Life Magazine in 1951 wearing one. Montgomery Cliff and Frank Sinatra were featured in the memorable motion picture From here to Eternity in Hawaiian-Print Aloha shirts.[74]

Beach Boys of Waikiki

Where there’s Aloha Shirts, there are Beach Boys. In trying to come up with a list of the Waikiki Beach Boys of the 1930s, I have relied on an email that came to me from Karen Cotter, assisted by her sister Emily Fradkin. An aunt of the two sisters was Emily Campbell Kauha Davis (1896-1987). A school teacher at 20, Emily sailed away to

“Anyway,” wrote Karen Cotter, “from amongst my aunt’s books I acquired two old poetry books by Don Blanding, published in 1923 and 1925 respectively, and in the back of one, written in pencil, is a list of ‘Beach Boys of Waikiki’ in my aunt’s hand which I thought you might find of interest...”

The listing – by no means complete, but still the largest list of 1930s Waikiki Beach Boys I have seen anywhere – is as follows, in the order it was written:

· Pua Kealoha

· Davd Kahanamoku

· Louis Kahanamoku

· Sergent Kahanamoku

· William Kahanamoku (whom Emily referred elsewhere as ‘Billy’)

· Sam Kahanamoku

· John Napahu

· John D. Kaupiko (who was married to Emily’s best friend, Helen)

· John Kauha

· Hiram Anahu

· William Keawemaha (nicknamed ‘Tough Bill’)

· ‘Steamboat’ Keawemaha

· Paul Tsang

· John Liu

· Chick Daniel

· Jeremiah Lima

· Joseph Guerrero

· Tony Guererrero

· George Harris

· Ilima

· Abe Umiamaka

· Louis Rutherford

· Enay MacKinney[75]

“For many years,” Emily’s niece Karen wrote, “my aunt wrote a newsy column in the Honolulu Advertiser in the ‘30s and ‘40s called ‘Beachwalk Girl.’ She often sent my mother columns which she thought my mother would enjoy – not all the columns for sure as I believe they were a daily item – perhaps only weekly, but we have a fat scrapbook full of the daily happenings in the neighborhood. My aunt lived on Seaside Avenue

“... perhaps the list will be of some use in your ongoing research. Thank you, Karen and Emily.”[76]

The Surf Ski

One of the few surf-related innovations and inventions of the 1930s that cannot be attributed to Tom Blake is the invention of the surf ski, normally credited to Dr. G.A. “Saxon” Crackanthrope, a stalwart of the Manly Club, N.S.W.,

The original design was 8 foot x 28 inches x 6 inches thick with 12 inches of tail lift, solid cedar planks and a double bladed paddle and footstraps.[77]

Other claims to the invention of the surf ski include: Bill Langford at Maroubra, pre-World War II; a 1934 design recalled by Denis Green of oil impregnated canvas stretched over a timber frame, again at Maroubra;[78]a type of ski used by two brothers at Port Macquarie N.S.W. on their oyster leases, and occasionally in the surf around 1930;[79]and a “first appearance on Newcastle beaches during the twenties, and came to Deewhy about 1932;”[80]as well as 1933, Jack Toyer of Cronulla.

Despite the competing claims, it was Saxon Crackanthrope who was the one to register and received the patent for the surf ski.[81]

The Surf-o-Plane

Another form of surf craft invented in

On a side note, an article entitled “Making Money at the Beach,” published in Popular Mechanics, July 1934, Volume 62 No. 1, pages 115 – 117, gave plans and specifications for making a solid wood “Bellyboard.”[83]

We now leave a general look at the mid-1930s and focus, again, on the surfers of the time…

[1]Warshaw, Matt. The History of Surfing, ©2010, published by Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco

[2]Lynch, Gault-Williams, et. al. TOM BLAKE: Journey of a Pioneer Waterman, ©2001.

[3]Vansant, Amy. “Dudley Whitman: A Visit with Florida

[4]Vansant, 1994, p. 84.

[5]Vansant, Amy, 1994, p. 84.

[6]Vansant, 1994, p. 84. Dudley Whitman quoted. Dudley was born March 20, 1920.

[7]Lynch, Gary

[8]Lynch, Gary

[9]Lynch, Gary

[10]Lynch, Gary

[11]Lynch, Gary

[12]Lynch, Gary

[13]Vansant, 1994, p. 85. Dudley Whitman quoted.

[14]Vansant, Amy. “Goofing Off In God’s Waiting Room,” or “Gauldin Reed: A Link to Florida

[15]Vansant, 1994, p. 85. Dudley Whitman quoted.

[16]Vansant, 1994, p. 85. Dudley Whitman quoted.

[17]Lynch, Gary

[18]Lynch, Gary

[19]Lynch, Gary

[20]Lynch, Gary

[21]Smiley, David. “Surfer, horticulturist William Whitman dies,” Miami Herald , June 1, 2007. See also The Whitmans at the First East Coast Surfing Championships, Daytona , Florida

[22]Karp, David. “Bill Whitman, 92, Is Dead; Scoured the Earth for Rare Fruit,” New York Times, June 4, 2007 with Correction Appended.

[23]Kahn , Jordan Daytona Beach become Florida

[24]Kahn , Jordan Daytona Beach become Florida

[25]Kahn , Jordan Daytona Beach become Florida

[26]Kahn, Daytona Beach

[27]Kahn, Daytona Beach

[28]Kahn, Daytona Beach

[29]Kahn, Daytona Beach

[30]Kahn, Daytona Beach

[31]Kahn , Jordan Daytona Beach become Florida

[32]“Roman Pools Are the Only Pools in This Area Devoted Exclusively to Water Sports.” See handbill, February 18, 1934. Tom had worked here before.

[33]Lynch, Gary Washburn , Wisconsin America

[34]Blake, Tom. Hawaiian Surfboard, 1935.

[35]Lynch, Gary

[37]Blake, 1935, 1983, p. 69.

[39]Long Beach

[40]Long Beach

[41]Long Beach

[42]Long Beach

[43]Long Beach

[44] Long Beach Press-Telegram, “Dozen Clubs in Surf Contests,” November 14, 1938.

[45] Long Beach Press-Telegram, “Dozen Clubs in Surf Contests,” November 14, 1938.

[46] Long Beach Press-Telegram, “Surfriders Watched By Big Crowd,” December 12, 1938.

[47] Long Beach Press-Telegram, “Surf Event Is Won By Hermosians,” December 4, 1939. This was the contest Tarzan had originally won entry to but had been initially denied. It would appear that he managed to be sent, after all, along with A.C. Spohler and Jack May. See chapter on Tarzan.

[48]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[49]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[50]See Verge, Arthur C. “George Freeth: King of the Surfers and California

[51]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[52]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[53]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[54]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego Imperial Beach lifeguard who lead the charge on the Tijuana Sloughs – in the 1930s and 1940s, California

[55]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[56]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[57]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[58]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[59]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[60]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[61]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[62]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[63]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[64]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[65]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[66]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[67]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[68]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[69]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[70]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[71]De Wyze, Jeannette. “90 Years of Curl,” San Diego

[74]A Brief History of the Hawaiian Aloha Shirt by Mickey Steinborn at www.mauishirts.com. See alsoHistory of Hawaiian Shirts from www.alohafunwear.com

[75]See comment by DeSoto Brown.

[76]Email from Karen Cotter, 2010.

[77]Maxwell, 1949, p. 245; Bloomfield, p. 69; Harris, p. 56. The footstraps addition, at this early stage, is questionable.

[78]Galton, p. 43.

[79]Wells, p. 160.

[80]Thomas, E.J. The Drowning Don’t Die – Fifty Years of Vigilance and Service by the Deewhy Surf Life-Daving Club, 1912-1962, ©1962, p. 31. Published by the Deewhy Surf Life Saving Club. Printed by the Manly Daily Pty Ltd. Hard cover, 54 pages, 33 two-tone photographs, executive officers 1912-1962.

[81]Wells, p. 155.

↧

↧

Canoe Drummond

Ron “Canoe” Drummond (1907-1996)

In his late 20s by the mid-1930s, Ron Drummond was born in Los Angeles , raised in Hollywood and, as a kid, summer vacationed at Hermosa Beach Southern California coastline, eventually canoe surfing waves as large as 15 feet.[1]

Ron was the quintessential “canoe surfer.”

“Well, I’ve been interested in canoeing ever since I was fourteen years old,” Ron told surf historian Gary Lynch in an interview eight years before his passing at the age of 89. “I remember my brother, Tommy. He’s older; year and a half older than I am. He says, ‘Aw, you’re dumb to try to go out in the ocean in a canoe.’ First time I brought a canoe down... we used to spend our summers at Hermosa Beach

The tall, lanky Drummond became a track star while attending UCLA in the mid-1920s, specializing in discus and the shot put. Throughout his life he continued to swim, canoe, and bodysurf on into his mid-80s.[3]

“I knew [Pete] Peterson when I was a kid in high school,” Ron recalled of that era’s most noted Southern Californian surfer. “His father owned the bathhouse at Crystal Pier in Santa Monica ; Ocean Park Chile

“Then, the first – second – date I had with Doris [Ron’s future wife], it was right after the Long Beach Terminal Island Doris . About a dozen people came over to talk to me, wondered who I was, never seen me before. I had a beard then.”[5]

“The first time I was on a surfboard, it was when I was a lifeguard,” at the Los Angeles

“I’ve always wanted to be an adventurer, you know,” Ron continued. “My father was an explorer… he’d been all over interior China, the Philippine Islands and all the out-of-the-way islands, and had skirmishes with headhunters, and all that sort of thing. Headhunters killed a lot of his men. [One time, they lost a guy] …and a fellow – native carrier that he had in his expedition – wanted to give him a Christian burial. So, Dad let them go in. They sneaked into the enemy camp – these headhunters’ camp [at night] – and they had their heads on poles and they were dancing around a big fire; real jubilant that they’d got these heads. So, the bodies were off in the dark… my father’s carriers got the bodies and my father took a picture of them carrying these bodies later the next day, stretched up, you know, like they put a deer on a pole: one end on one fellow’s shoulder and one on the other… they were holding their noses... hot climate... [the dead bodies] were putrid.”[7]

“But anyway, all I was going to say is, I wanted to be an adventurer, too. So, that’s why [when] I was studying mechanical engineering at UCLA… I just figured, well, [mechanical engineering] really doesn’t interest me... So, I heard that Eastern Canadian Mining Company was sending canoe expeditions out to unexplored areas to get the geology of it, so if they ever found anything that was favorable for the deposition of minerals, why, they’d send probably 40-50 prospectors in there. So, I saw the manager of this company when he came out to Los Angeles

“The result was, my career partner, Jack Barrington, had been the first white man on five rivers of northern Canada Barrington River Copper Needle River Copper Needle River

In 1931, Ron was the first one to publish a primer on bodysurfing, entitled The Art of Wave Riding.[9]At 26 pages and a print run of 500 copies, the small book is one of the first books ever published about surfing. “One feels sorry for those who have not learned to enjoy surf swimming,” Ron wrote in his intro. “To spend a day in the sand developing a ‘beautiful tan’ is pleasant; but the real pleasure of a trip to the beach is derived from playing in the breakers.” Elsewhere in the book, Drummond defined “glide waves” and “sand busters” and step-by-step bodysurfing instructions. Understandably, this booklet has become a prize amongst collectors.[10]

“I started to tell you why I’m deaf,” Ron kept on track with Gary Lynch. “I got hit by lightning and it knocked me about 15 feet flat on my back, and I’ve never been able to hear good since. It was such a loud noise, you know, when you hear thunder way off how loud it is, but when it’s right next to you, why, it ruined the nerves in my ear, so I’ve never been able to hear well since.”

“When was this?” asked Gary

“Oh, this was during the war, World War II, down in Port of Spain , Trinidad .” Like others of his generation, Ron was drawn into World War II, although he was already into his 30’s, age-wise, at war’s start. “I was unloading pillboxes and tanks and things like that from a ship, and the boom came up over that ship. It had a sealed deck, and then slings came down. I was just reaching for a sling to hook up a pillbox, and my hand was about six inches, I guess, from the sling. If I’d had it six inches farther – if I’d had a hold of that sling – it would have killed me, because it burned that sling almost completely through, three-quarter inch sling. Where it was up against the edge of the bit. I was lucky there... That’d be one of my close calls, I guess.”[11]

Drummond’s “close calls” did not keep him from seeking bigger and bigger surf to paddle his canoe into. During and after the war, he joined a select group of Southern California’s best watermen to ride California

“Back in the early ‘40s I surfed the Sloughs when it was huge,” Lorrin ‘Whitey’ Harrison told Serge Dedina in 1994. “It was all you could do to get out. Really big. We were way the hell out. Canoe Drummond came down.”[12]

“We paddled out and the surf was probably about 20 feet high or so,” Ron remembered. “I looked out about a mile where some tremendously big waves were breaking. I asked if anybody wanted to go out there with me, but nobody did. So, I went in my canoe and paddled out there. I set my sights in the U.S. and in Mexico

Ron went into a little more detail with Gary Lynch, probably talking about the same wave: “Did I ever tell you about the big wave I caught in a canoe down in the Tijuana Slough? … Boy, that was a whopper. That was about forty feet high, I guess. I was right inside the curl. Boy, I thought I was never going to make it… That was [another] one of my close calls… I guess.

“Dempsey [Holder] was the chief lifeguard down there…” On the day when Tommy Zahn and Peter Cole came out, after Dempsey had called them to get down to Imperial Beach pronto, Tommy and Peter paddled out, were amazed at the size of the waves and further amazed to find Drummond already out there… “out there where the big waves were breaking, ‘cause Dempsey talked to me later and he said I’m the only one that had ever ridden those big waves. They were about 20 feet high in near shore. That’s where he was, I guess.

“Well, a 20-footer is a good wave, but they’re about twice that big outside. None of the fellows would go out there with me. They’re scared of them. They can see they are just booming over thick like that… you could run a freight train through the curl.”[14]

Canoe Drummond is generally recognized with having ridden his canoe in surf as big as 15-feet. He and his Canadian style canoe were featured in a 1967 issue of Surfer magazine. He also appeared in two surf movies: Big Wednesday (the Severson flick, 1961) and Pacific Vibrations (1970). He continued to swim, canoe and bodysurf into his mid-80s. In 1990, he appeared in a Nike ad featuring senior surfers that ran nationally within the U.S.

Links:

Capistrano Flip: http://www.canoekayak.com/canoe/capistranoflipcanoe/

Classic in-water shot: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_snK4FObvgXg/SuJMuIfbM0I/AAAAAAAAAWc/Zkv3t_pgRw8/s1600/rondrummond.jpg

Action in-water shot: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_Y1TSrohwgZQ/S6qB8z8PgiI/AAAAAAAAA9o/yefO-bY7kjc/s1600/Gem-of-the-week.jpg

Same shot, reduced: http://www.surfingheritage.org/2010/03/ron-drummond-canoe-surfing.html

[1]Warshaw, Matt. The Encyclopedia of Surfing, ©2003, p. 168.

[2]Lynch, Gary

[3]Warshaw, Matt. The Encyclopedia of Surfing, ©2003, p. 168.

[4]Lynch, Gary

[5]Lynch, Gary

[6]Lynch, Gary

[7]Lynch, Gary

[8]Lynch, Gary

[9]Drummond, Ronald B. The Art of Wave Riding, ©1931, Cloister Press, Hollywood , California

[10]Warshaw, Matt. The Encyclopedia of Surfing, ©2003, p. 168.

[11]Lynch, Gary

[12]Dedina, Serge, 1994, p. 37. Lorrin Harrison quoted.

[13]Dedina, Serge, 1994, p. 37. Ron “Canoe” Drummond quoted.

[14]Lynch, Gary

[15]Warshaw, Encyclopedia of Surfing, ©2003, p. 168.

↧

Surfari to Newquay, 1929

This grainy film captures the moment when Lewis Rosenberg attempted stand-up surfing for the first time in Britain. The video was taken in 1929 and records the travels of three friends who caught the train from London to Newquay in Cornwall after Rosenberg saw film from Australia and carved a home-made board from balsa wood:

You can read more about this here: http://www.museumofbritishsurfing.org.uk/2011/06/30/standing-proud/

You can read more about this here: http://www.museumofbritishsurfing.org.uk/2011/06/30/standing-proud/

↧

Sean Collins (1952-2011)

↧

↧

2011 Passings

In remembrance of all of the friends and family members that left us and are now riding the great wave in the sky. We miss you, we love you, your thoughts and memories will always be with us. Aloha

↧

Australian Surfing, 1912

First known picture of Australian surfing: Tommy Walker, 1912:

And article about it:

And article about it:http://www.surfertoday.com/surfing/6670-australias-first-surfing-photograph

↧

Harold Iggy Ige

↧

1930s: Prelude

The human act of riding ocean waves on floatation devices has been going on for thousands of years. We, in fact, do not know how many thousands of years. It has been reasonably estimated that the act involving wooden boards could date as far back as 2000 B.C. (4000 B.P.), before the beginning of the Polynesian migration across the Pacific Ocean .[1]If we count canoe surfing, the act must be far older than that and if we include bodysurfing, then we must consider the span of time in terms of tens of thousands of years.

Surfing on boards – he’e nalu– rose to a high level of development in the Hawaiian Islands sometime after Polynesians first settledthe Hawaiian chain beginning around 300 A.D. (2300 B.P.). “Wave sliding” using boards – along with canoe and body surfing – not only became important parts of the lifestyle of all Hawaiians prior to European contact in the later 1700s, but was also integrally connected with Hawaiian culture.[2]In stark contrast to this “golden age,” surfing fell to an almost ignominious near-death during the 1800s – mostly due to European and American cultural, political and religious influences.[3]

During “The Revival” period of surfing at the very beginning of the Twentieth Century, surfing’s decline was arrested and set back on a course of natural evolution. Since that time, surfing has grown vastly in popularity and now is practiced in most every corner of the world. Key figures in this resurgent interest in surfing include: George Freeth, Alexander Hume Ford, Jack London, Duke Paoa Kahanamoku, Dad Center , Dudie Miller, “John D” Kaupiko and numerous beach boys and surfing wahines at Waikiki , on O’ahu, in the first two decades of the 1900s.[4]

A little surprisingly to those of us looking back at it now, surfing’s growth was not explosive following its resurgence, but rather a slow and gradual progression. For this reason, the surfing years between 1912 and 1928 are not well known and, predictably not well documented.[5]

We, of course, know the historical context. The 1910s were dominated by events that would lead to the First World War. The war, itself, was vastly different than any other war that had preceded it. “The total number of casualties, including killed, wounded, and missing, is figured at 37.5 million… An outbreak of influenza in the autumn of 1918 compounded the death toll as it swept through populations already weakened by the nutritional privations of total war.”[6]

In Europe and other nations that had been caught up in the global struggle, “Wartime disruption helped cause a sharp recession in 1920-21… For most nations, prosperity returned only in the mid-1920s.”[7]

“The catastrophic toll of the war also resulted in a new, looser code of morality, especially in a growing urban environment. A new generation, decimated by war, felt betrayed by their elders and rejected the more austere standards of conduct they had been taught as children.”[8]

To truly appreciate the great surfing decade that the 1930s was, it is important to understand this time leading into it, in the Earth zones where surfers were riding waves in the Hawaiian style: Australia, Southern California and – of course – Waikiki.[9]

Australia

It is still a common misconception that surfing in Australia began in 1914-15, with the visit of Duke Kahanamoku to New South Wales and the surfing demonstrations he gave at that time. In fact, Australia Hawaii

Australian surfing’s Polynesian connection came in the form of Alick Wickham and Tommy Tana. In the 1890s, Alick Wickham, a native of the Solomon Islands

Around the same time another South Sea Islander, Tommy Tana – a youth employed as a houseboy in the Manly district – was body surfing at the beach there. Tana hailed from the Pacific island of Tana , in the New Hebrides, which is now called by its traditional name of Vanuatu Manly Beach Manly Beach

After the turn of the century, Alick Wickham shaped the first surfboard in Australia Solomon Islands

When more novice swimmers and non-swimmers started ocean bathing off unsupervised beaches, accidents became numerous and soon raised hell with the public.[15]At Manly Beach

By 1909, the newly formed Australian Surf Life Saving Association published that there were eleven clubs active in New South Wales Australia New South Wales

The first Surf Carnival was held on January 25th 1908 at Manly Beach

That same year, Alexander Hume Ford– the man who more than anyone helped publicize surfing at Waikiki during the first two decades of the Twentieth Century – visited Manly. He wrote, curiously, that “I wanted to try riding the waves on a surf-board, but it is forbidden.”[19]

Many writers – including myself, once upon a time – have written that before Duke Kahanamoku came to Australia

While assisting with the 1908 trade agreements between Hawai’i , Australia and New Zealand Australia again in 1910, he noted that there were already several surfboards stashed at Manly Beach Australia

During this time, amongst some surf lifesavers, there was an understanding of what surfboards were. It was noted that “Fred Notting painted a brace of slabs and named them Honolulu Queen and Fiji Flyer; gay they were to look at but they were not surfboards.”[21]

In 1912, well-known Australian swimmer, local businessman and politician[22]Charles D. Paterson, of Manly Beach , Sydney , brought a solid, heavy redwood board back with him from Hawai’i

Yet, Patterson and his mates were not the only ones who had attempted surfboard riding or were surfing prior to Duke’s visit. Early in 1912, the Daily Telegraph reported on the second Freshwater Life Saving Carnival held on January 26th. In the account of the day’s events, there is mention of surfboard riding: “A clever exhibition of surf board shooting was given by Mr. Walker, of the Manly Seagulls Surf Club. With his Hawaiian surf board he drew much applause for his clever feats, coming in on the breaker standing balanced on his feet or his head.”[24]Whether the board Walker

We do know for sure that following the arrival of C.D. Paterson’s board at Manly in 1912, a small group – the Walker Brothers, Steve McKelvey, Jack Reynolds, Fred Notting, Basil Kirke,Jack Reynolds, Norman Roberts, Geoff Wyld, Tom Walker, Claude West (then aged 13) and Miss Esma Amor – all attempted surf riding on replica boards. Some of these tried surfing before and some after Duke’s visit. Made from Californian redwood by Les Hinds, a local builder from North Steyne , they were 8 ft long, 20” wide, 11/2” thick and weighed 35 pounds. Riding the boards was limited to launching onto broken waves from a standing position and riding white water straight in, either prone or kneeling. Standing rides on the board for up to 50 yards/meters were considered outstanding.[25]

In Queensland Tweed River

So, yes, surfing on wooden boards – or their facsimile – had already begun by the time Duke Kahanamoku first visited Australia Australia New South Wales

Duke Kahanamoku’s tandem partner while in Australia , Isabel Letham, continued board riding at Freshwater up to 1918 when she moved to the USA

Circa 1915, seventeen year old Grace Wootton (nee Smith) was encouraged to try prone boarding – body boarding – at Point Lonsdale , Victoria Australia by “a Mr. Jackson and a Mr. Goldie from Hawaii

Following Duke’s surfing demonstrations in Australia and New Zealand

Circa 1915, Collaroy Surf Life Saving Club member, Alf “Weary” Lee saw Duke Kahanamoku’s Dee Why demonstration and built his own board according to Duke’s design. Since the board was stored in the club house, it was available for younger club members to have a go of it.[34]

Duke’s most stoked pupil, Claude West, was initially at the Freshwater Club but later moved to Manly. He became Australia Palm Beach Manly Beach

In Queensland

In 1919 Louis Whyte, a Geelong Lorne Point , Victoria

John Ralston, a Sydney solicitor and land developer, introduced surfboards at Palm Beach , Sydney Palm Beach

Some of the Surf Life Saving clubs became centers of board riding, clubhouses becoming storage facilities for boards, in addition to being places where club members could gather and hang out.[40]

With the end of World War I in 1918, military technological developments like industrial glues and varnishes were applied to marine craft, including surfboard construction.[41]

In the early years of its establishment, board riding was given little support by the Surf Life Surfing Association. Competitions as part of carnivals were judged subjectively. For example, a headstand scored maximum points although it had little to do with how well one rode the wave. With a growing emphasis on rescue techniques, it was paddling skill that became the focus when it came to surfboard use. Record keeping for surfing events was an after thought. Often, board events were either not held or not recorded, and since the ASLA was in its infancy and basically a New South Wales

Amazingly, it was not until 1946 that the first officially-recognized Australian Longboard Championship took place.[42]However, the first credited Australian surfing magazine was published in 1917. This was Manly Surf Club’s The Surf, which first published on December 1, 1917. It ran for twenty editions, until April 27, 1918.

In February 1920, Claude West used his board to rescue a swimmer at Manly. The rescuee was the Australian Goveror-General, Sir Ronald Mungo Fergerson, who presented his rescuer with his silver dress watch, in appreciation.[43]

A newspaper report of the “Australian Championships” at Manly, March 1920, records the results of a surfboard race:

1. A. McKenzie (North Bondi )

2. Oswald Downing (Manly)

3. A. Moxan (North Bondi )[44]

A similar newspaper report of the Bondi Championships, April 1921, records the results of a surfboard race as:

1. A. McKenzie (North Bondi )

2. A. Moxan

Other starters were Oswald Downing and Claude West (Manly).[45]

By 1921, the Surf Life Saving Association printed their first handbook. It probably formed the basis for subsequent publications later entitled the “Handbook of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia.”

At the Australian Championships at Manly in 1922, the board event results were:

1. Claude West (Manly)

2. A. McKenzie (North Bondi )

3. Oswald Downing (Manly)

West, who had apparently dominated the demonstrations, was soon to retire.[46]

Oswald Downing was an early board builder and a trainee architect who had drawn up his own surfboard construction plans. These are possibly the plans printed in the 1923 edition of The Australian Surf Life Saving Handbook.[47]

In celebration of Collaroy SLSC’s victory in the Alarm Reel Race at the Australian Championships at Manly in 1922, swimmer Ron Harris’ family commissioned Buster Quinn (a cabinet maker with Anthony Hordens) to make a surfboard. Quinn made the board from a single piece of Californian Redwood at the Dingbats’ Camp. Before it was completed, however, Harris’ father died and the family left Collaroy. Chic Proctor acquired the board in Harris’ absence and it remains in the clubhouse to this day as the Club’s Life Members Honour Board.[48]

With growing numbers of surf board riders, the Manly Council considered banning surfboards altogether, in 1923, in the interest of the public safety of bodysurfers. This idea was forgotten when one day at the beach, three city councilors witnessed a rescue of three swimmers in high surf by Claude West using his surfboard. Reversing their position, the Council commended the use of surfboards as rescue craft.[49]

At the 1924 the Australian Championships at Manly, the surfboard display was won by Charles Justin “Snowy” McAlister of the Manly Surf Club. As a kid, he had watched Duke ride in 1915. Thereafter, Snowy soon began surfing on his mother’s pine ironing board. “I used to wag school and rush down to the beach with it,” he recalled. “I got away with it a number of times, but she eventually found out because I would come home sunburnt.”[50]The pine ironing board was followed by a self-made plywood board and his first full size board, a gift from Oswald Downing.[51]

Later, Snowy made his own solid redwood board. “I used to go into the timber yards in the city and buy a ten by three foot piece of wood about two feet thick (sic, inches?), which I had delivered to the cargo wharf beside the Manly ferry.

“I’d lug it home, then carve it, varnish it overnight and try it out the next morning.

“We were getting murdered in those days.

“The boards had no fins.

“We’d go straight down the face of the wave instead of riding the corners as the Duke had done. When we saw him do that we thought he was just riding crooked.”[52]

Starting out on an impressive competitive record, Snowy McAlister won board displays in Sydney in 1923-24 (Manly), 1924-25 (Manly), 1925-26 (North Bondi) and 1926-27 (Manly, second Les Ellinson).

His record at Newcastle South Africa and England on the way to the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928, accompanying another Manly Surf Club member Andrew “Boy” Carlton Australia

Another noted surfer of this formative period in Australian surfing was Adrian Curlewis. Around 1923, Curlewis bought a used 70 pound board from Claude West, so he could surf regularly at Palm Beach North Steyne for five pounds and fifteen shillings, including delivery.[55]Curlewis became a noted surf performer, becoming somewhat of a star thanks a photograph printed in an Australian magazine in 1936.[56]

Sir Adrian Curlewis was born in 1901. He graduated from Sydney University Malaya in World War II and was a prisoner of war from 1942 to 1945. He held the Presidency of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia from 1933 to 1974, his position as sole Life Governor of that Association from 1974, and his Presidency of the International Council of Surf Life Saving from 1956 to 1973. Curlewis served as a New South Wales District Court Judge from 1948 to 1971, retiring at the age of 70.[57]Perhaps because of his early board riding experiences and long association with surf lifesaving organizations, he was a noted 1960s opponent of the growth of an independent surf culture centered on wave riding.[58]

At Coolangatta, boardriding continued to expand during the 1920s. Basic competitions (using a standing take-off) were organized and riders included Clarrie Englert, Bill Davies, “Bluey” Gray and later, Jack Ajax

North of Coolangatta, the first full-sized board was probably owned by John Russell of the Main Beach Club, circa 1925.[59]

Circa 1925, Sydney rider Anslie “Sprint” Walker surfed at Portsea , Victoria

The North Steyne Surf Life Saving Club promoted their 4th annual carnival, scheduled for December 19, 1925 at 2:45 p.m., with a flyer printed by the Manly Daily Press. The noted “Surf and Beach Attractions” included: “1200 Competitors, 18 Leading Surf Life Saving Clubs Participating - Surf Boat Races, Thrills and Spills, Board Exhibitions, All State Surf Swimming Champions Competing.”[61]

The Australian Surf Life Saving Association promoted their annual surf championships, scheduled for February 27, 1926 at 2.30 p.m., with a flyer printed by the Mortons Ltd. Sydney. It emphasized: “Surf Boats, Surf Shooting and Surf Board Displays by Real Champions.”[62]

In the late 1920s, Collaroy SLSC member Bert Chequer manufactured surfboards commercially and 15 shillings cheaper than North Steyne builder Les Hind.[63]In the early 1920s, Chequer had been captivated by the likes of board riders such as Weary Lee, Chic Proctor and Ron Harris and made his first surfboard at 17 using a design similar to Buster Quinn’s. As the years progressed, Chequer refined Quinn’s design, producing a board which was held in high regard by many other board riders in the Club. Dick Swift requested he build him a board (the board is still in the Club house) and with delivery of the board a flood of similar requests came his way. So, with this development and little work in his father’s building business to keep him busy, Chequer decided to try his hand at commercial surfboard building – one of the earliest such enterprises in the country. The cost of a Chequer board was £5 which included delivery.

Chequer bought his timber from Hudson

Chequer was soon supplying individuals and clubs up and down the New South Wales coast and as far away as Phillip Island in Victoria

In the late 1920s, T.A. Brown and A. Williams used a corkwood board from Honolulu

Eric Mallen purchased a cedar slab that was once the counter of the Commerical Bank, and had it shaped into a fouteen foot board by Jack Wilson. Proving to be too unwieldy, the board was later cut down, decorated and named “Leaping Lena.” On large days, Eric Mallen would leap off the end of the large jetty that ran out from Main Street

On Sunday, April 26, 1931, a belt and reel rescue attempt at Collaroy in extreme weed and swell conditions resulted in the death of Collaroy SLSC member, George “Jordie” Greenwell. Even though the use of the reel was questionable in thick weed and high swell conditions, the inability of Greenwell to release himself from the belt was the main reason for his demise. Despite demands on the SLSA’s Gear Committee, the “Ross safety belt” – designed to ensure the lifesaver from just such an entanglement – did not become compulsory for member clubs until the 1950s. Greenwell was posthumously awarded the Meritious Award in Silver, the SLSA’s highest honor.[69]

While Greenwell’s drowning resurrected the debate on surf belts, there were two more immediate and positive developments from the drowning. The first was an intensification of Association trials using waxed line to see if it would “overcome the difficulty of seaweed.” The other was the Association’s endorsement of the use of surfboards as life saving equipment. In the Greenwell drowning itself, the surfboard had proved its usefulness in surf with a high seaweed content.